Antarctica and the South PoleMap

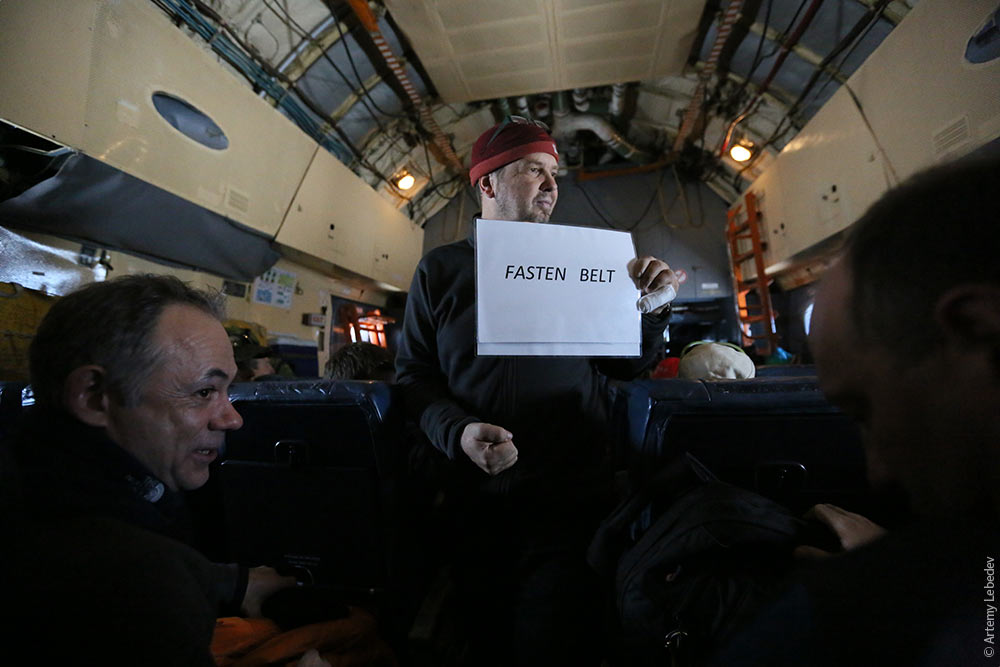

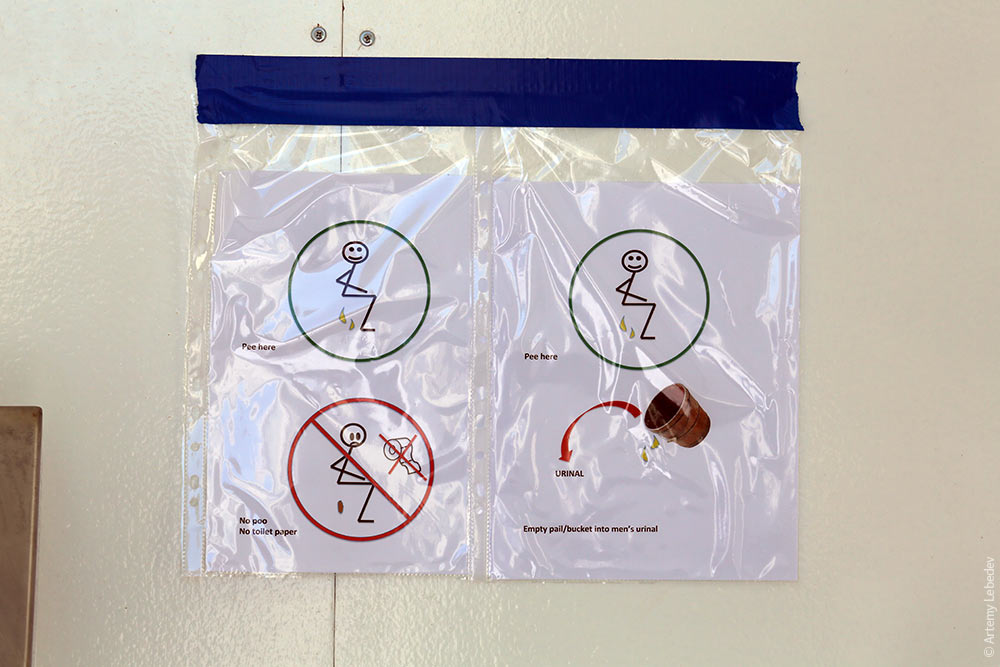

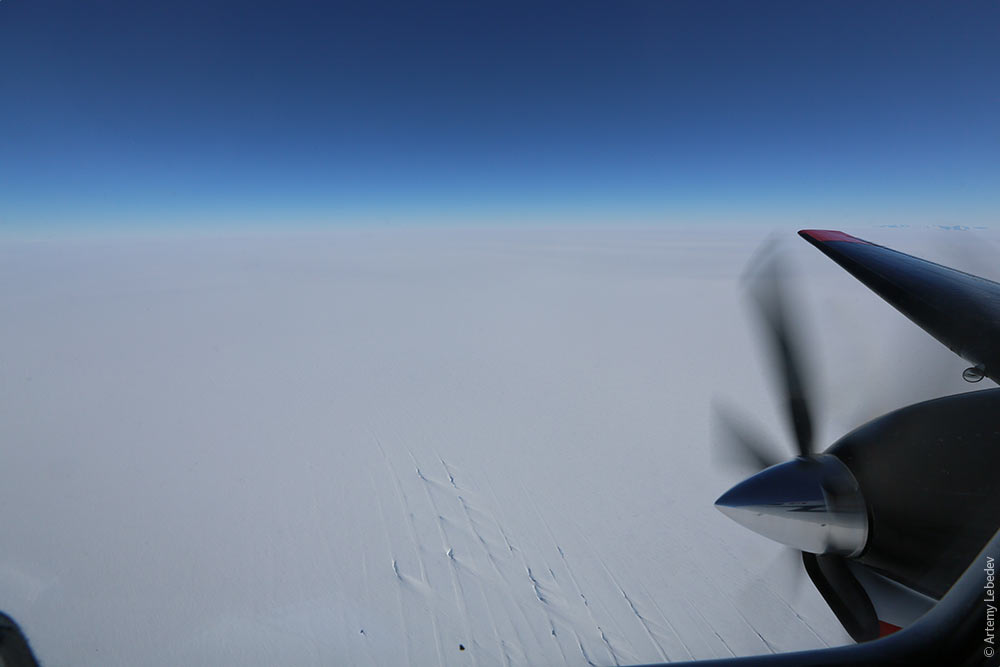

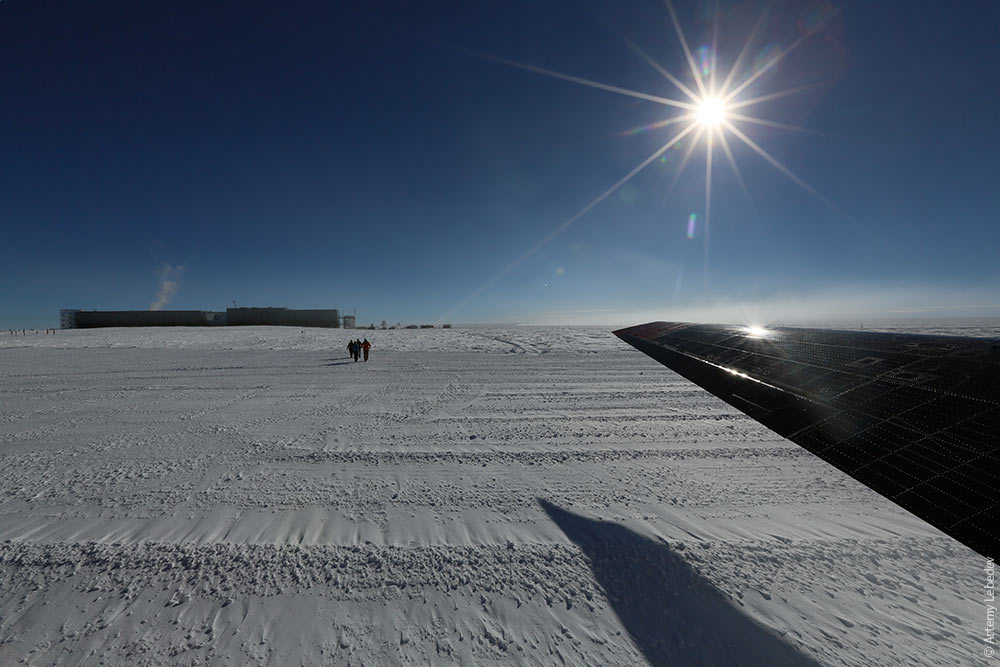

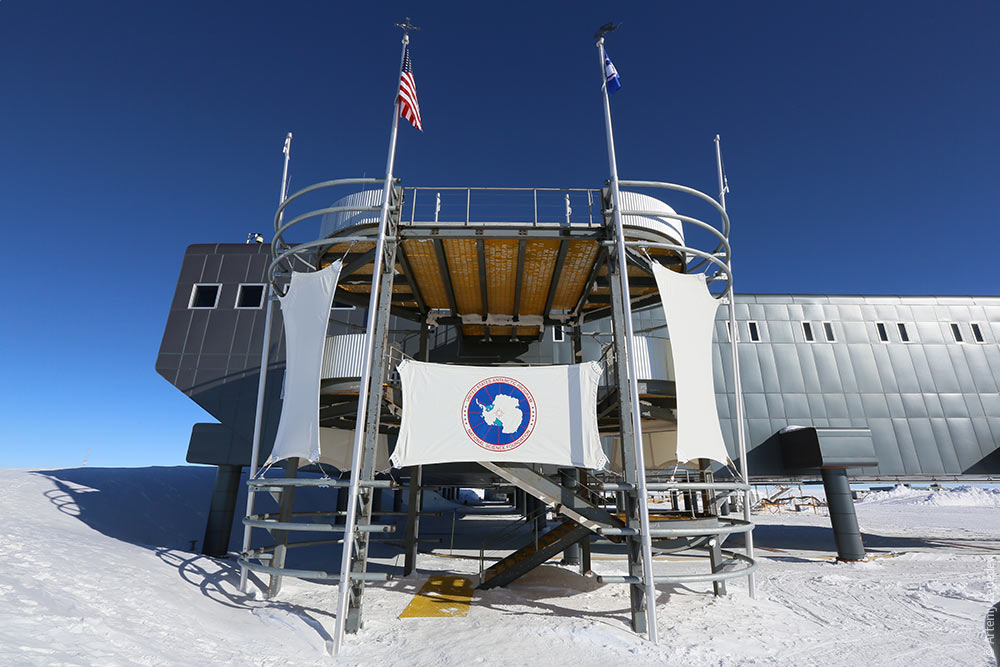

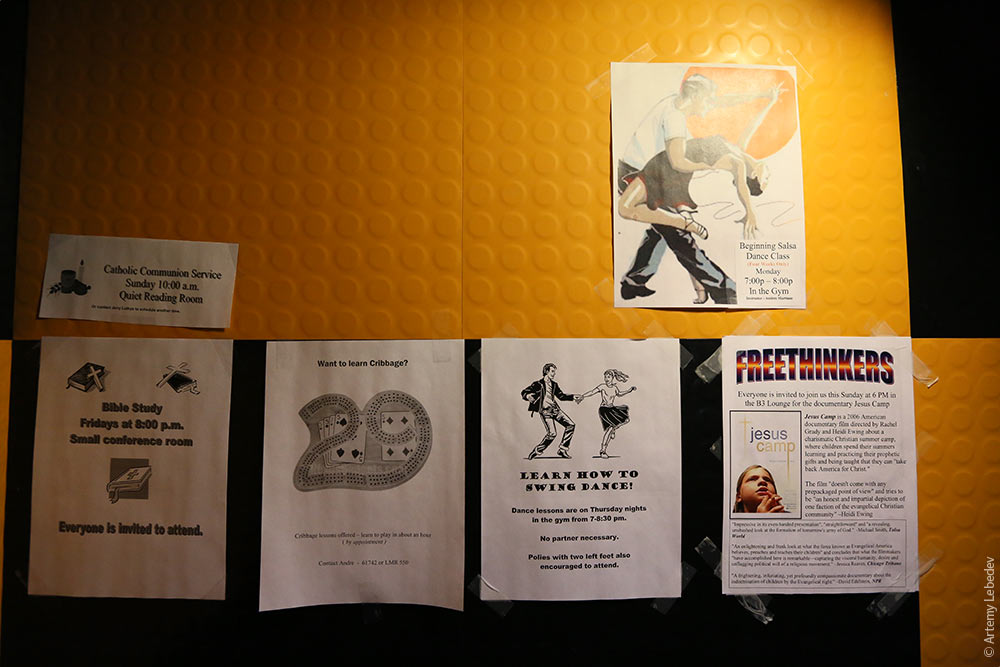

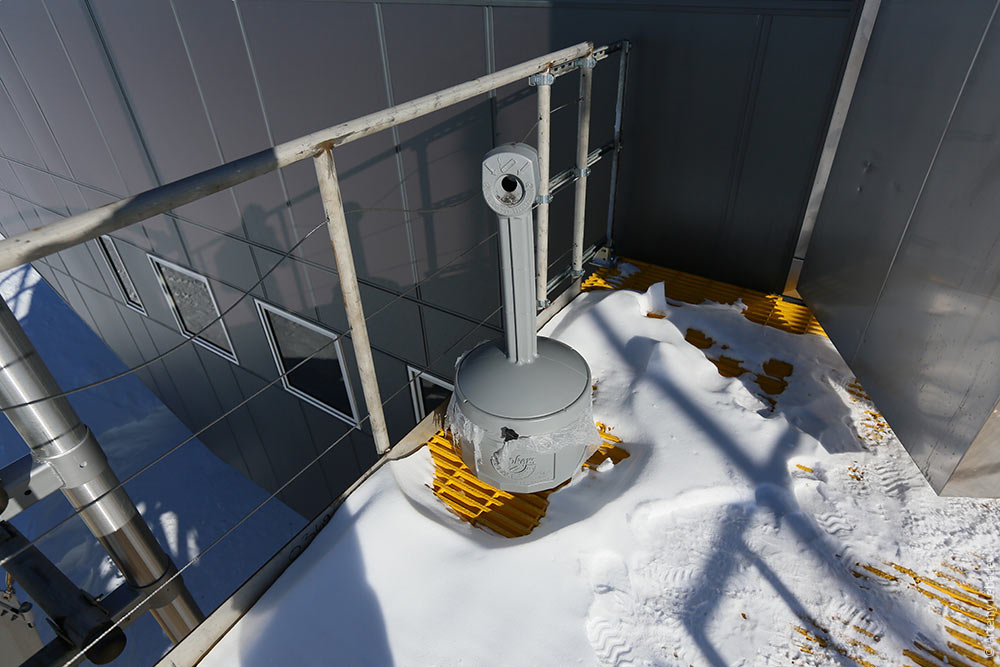

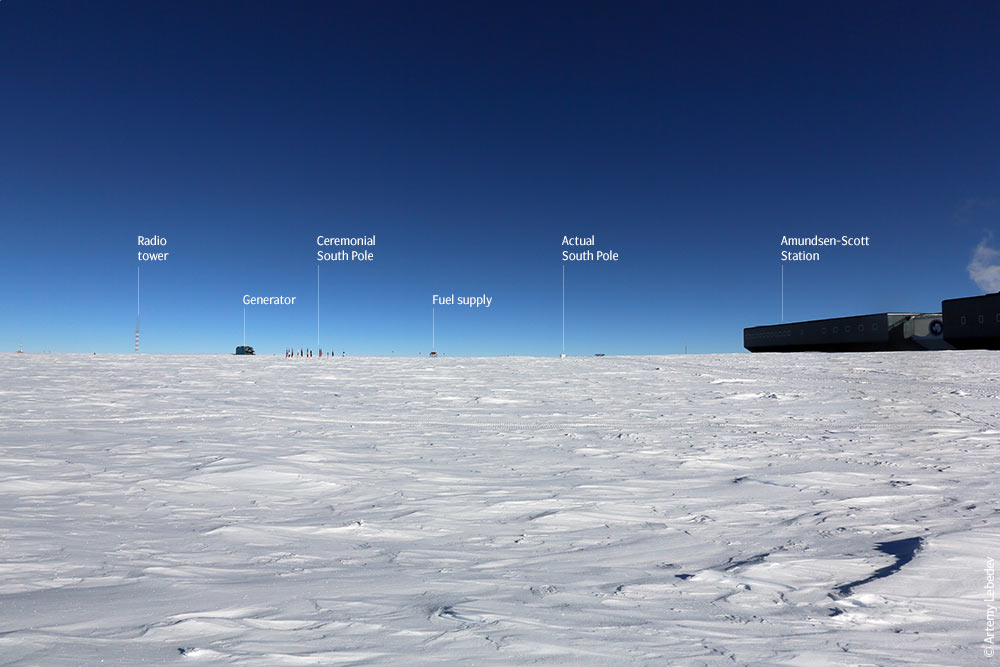

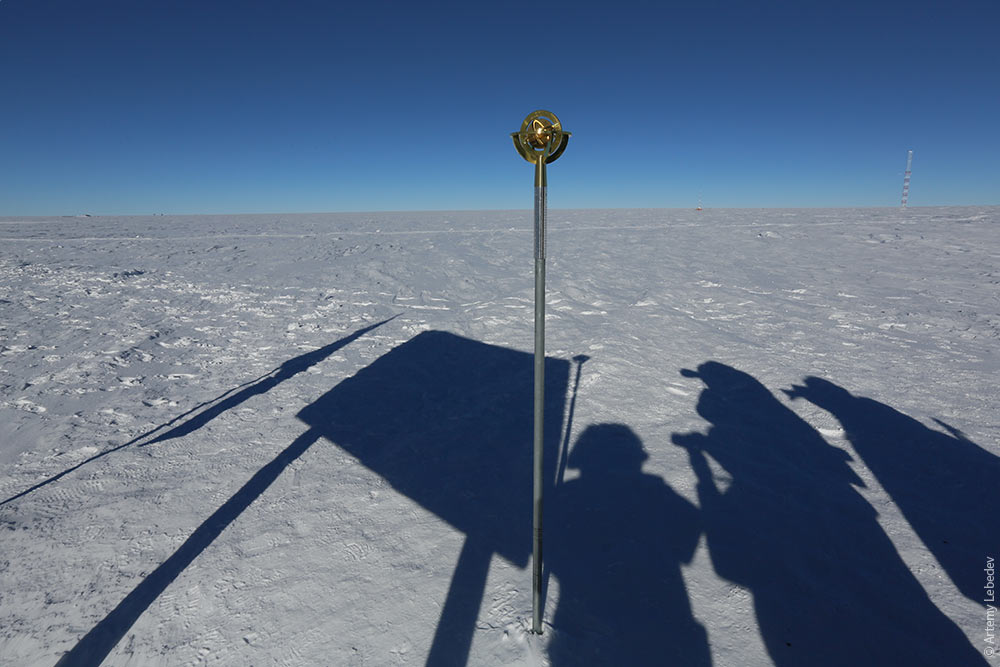

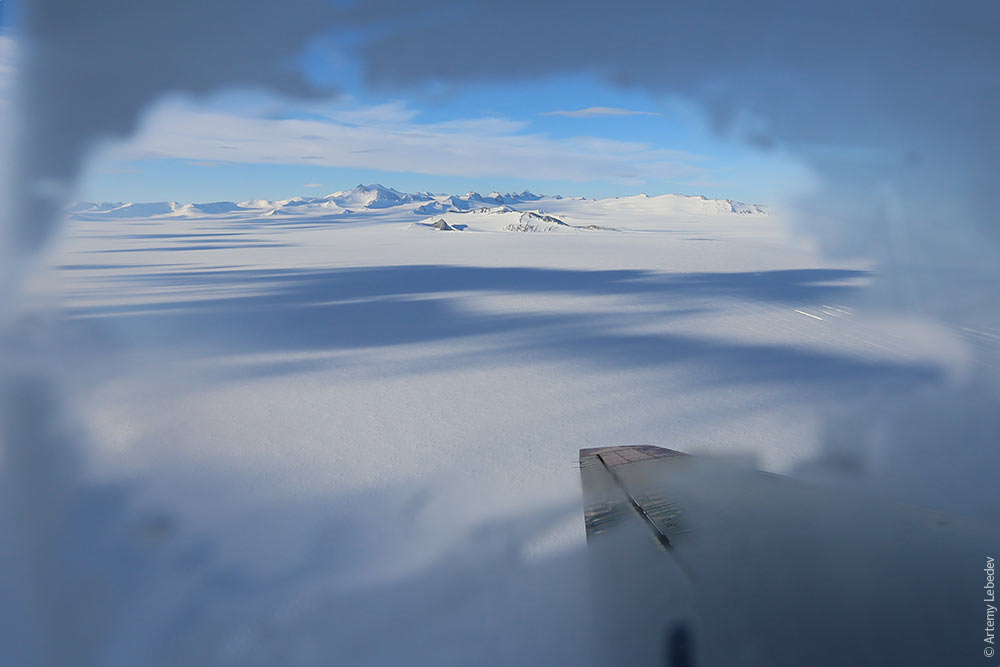

December The first people in the world to reach the South Pole were Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his five companions. This was 101 years ago, on December 14, 1911. Because all Amundsen had with him was a sextant (his theodolite had broken), it took three days of calculations to find the correct spot. The explorers celebrated with cigars. Amundsen knew that Englishman Robert Scott was also making his way here. So he left behind two letters inside a tent next to the Norwegian flag. Thirty-three days later, Scott’s expedition reached the South Pole and discovered the two letters. In the first, Amundsen asked Scott to deliver the second letter to the King of Norway. On the return journey, Scott’s expedition kept losing man after man until all had died a tragic and heroic death. Their bodies were later discovered in a snow-covered tent along with Amundsen’s letters and Scott’s diary. * * * Today, a journey to the South Pole is the most expensive trip in the world. Approximately 50,000 people visit the shores of Antarctica on cruise ships every year to see the penguins, only a few hundred travel deeper into the continent, and less than a hundred make it all the way to the South Pole each year. The minimum amount a tourist can expect to pay is $40,000 (for reference, a trip to the North Pole costs five times less). There are two companies which arrange trips for tourists: one from Chile through the American polar station, the other from South Africa through the Russian station. They make no attempt to compete on price—the Antarctic mafia is busy at work. I flew through the Americans. A Soviet Ilyushin Il-76 aircraft, snatched up by American Mormons from Kazakhstan immediately after the collapse of the USSR, performs flights from Punta Arenas to Union Glacier, where the campsite is located. The flight costs $10,000 each way. In full accordance with custom, the Russian crew flies with the obligatory Orthodox icon on the dashboard.  A meal is offered on the flight: attendants prepare sandwiches with rubbery sliced bread and margarine, because they cut costs on absolutely everything. When you’ve got yet another group of rich tourists going to the edge of the world, you can make their conditions as extreme as you like—no one will say a word.  Fasten belt. The plane will be landing soon.  The plane lands right on the ice. The runway is prepared anew every year, but it doesn’t take much work—the surface is already even.  Before each landing, a special vehicle resembling a golf cart drives over the landing strip with a fault detector to verify the integrity of the ice.  Antarctica—how exciting. I’ve dreamt of coming here for so long. I packed three pairs of pants, thermal underwear, sweaters, three pairs of mittens and gloves, two balaclavas, and a ski mask. The temperature in camp: −9 °C.  Food and drink supplies are loaded onto a tractor-pulled sled. An off-brand version of Pringles. Canned ham. The cheapest wine in the world, at $1 a bottle (even though they bring it here from Chile, where for $3 you can already find something decent).  A traffic sign.  The camp is staffed mostly by women. They get the task of unloading the cargo.  Tourists are assigned to their tents in pairs. The camp’s staff also lives in tents, but theirs are one and a half times smaller.  Inside the tent are two camping beds, a little table, and a trash can. Sleeping bags are rented separately.  Because this is the Antarctic summer and the sun never sets, there’s no need to heat the tents: they’re warmed sufficiently by the sunlight, it’s about 15 °C inside. The dead of night:  Barrels of fuel are shipped in at every available opportunity.  The gas station.  Solar panels are actively used. Every economy of fuel counts.  There are plenty of snowmobiles, cars, tractors, and other transport.  Both wheeled and tracked vehicles are used.  The camp has its own fleet of aircraft. The planes are used to fly to the Pole, as well as to other locations: for example, to drop off tourists wishing to take a week-long stroll through the local mountains.  All the existing small structures are on sledge runners; automotive equipment and other heavy and large objects are left behind for the winter. In the winter, it’s −60 °C here and pitch black. Laundry hung outside dries in a day.  The dining tent. The food isn’t just unappetizing, it’s unbelievably, off-the-charts terrible. Canned sardines and ramen noodles are outright delicacies compared to the fare served up by the kitchen, whose cooks manage to make even pasta completely inedible.  Perhaps this partially has to do with the fact that the water is obtained from snow instead of ice. The snow tastes terrible, while the ice is like spring water. Although no, the pasta was still made from blotter paper.  Since the company is American, they begin torturing participants with questionnaires, briefings, lists of rules, etc. long before the trip even starts. Don’t go there, don’t cross this, don’t bring more than a liter of alcohol with you from the mainland. At the camp, they taught everyone how to use a sleeping bag. Typical American bullshit, in other words.  The bathroom rules are interesting. You’re supposed to do number one and number two separately. Poop and toilet paper drop down into the container under the toilet. Pee goes from the urinal into a separate tank. It’s trickier for women: you have to first pee in the toilet, then take the bucket under it and pour the liquid out into the urinal.  At night, you can’t just step out onto your front porch and take a leak outside your tent—this is Antarctica, after all. You have to use a bottle and then empty its contents into a special tank outside. Graywater from brushing your teeth is supposed to go here as well. I forget why exactly you can’t mix liquid and solid waste. Either way it’s all going to be loaded onto a plane and sent to the mainland, where it’ll be dumped on the ground at the first available opportunity. Even in space, the attitude towards excrement is more relaxed: just dump it overboard and you’re good to go.  After a nauseating dinner with revolting wine, it’s time for sleep. Morning greets us with a breakfast that’s downright offensive. The weather at the Pole is good, so we can fly out. A waifish blonde is handed a container with a dozen large hot water bottles—here, carry these to the plane.  The hot water bottles are used to thaw out the windows in our wonderful DC-3 aircraft.  Enema-patterned frost ornaments.  We fly for four hours.  Our airplane, by the way, was manufactured in 1941 but completely revamped recently: the wings and fuselage were extended, new engines and other innards were put in. Below us are natural faults in the ice.  A view of the U.S. South Pole station. Not just one tent, as some might think. 150 people work here in the summer and 50 stay for the winter.  We land on the South Pole.  Representatives from the station come out to greet us. The woman’s face and hair are covered with a thin layer of frost.  This young man came outside wearing a fleece and Crocs. It’s incredibly warm out: only −25 °C. And no wind. People here are usually glad to duck back into shelter after three minutes outdoors.  The U.S. station is named after Amundsen and Scott. It sits on hydraulic stilts (compare with the story about Yakutia). As snowdrifts bury the building over time, the stilts can be raised to maintain elevation.  The entrance resembles a safe door. It’s very cold here in the winter and airplanes don’t fly for half the year.  Inside, the style is a cross between an American office and a school.  The staff has decent entertainment options. A music studio.  A gym.  Various dance classes, clubs, talks.  The hospital.  The cafeteria.  A store that sells food, clothing and souvenirs. Alcohol is also available, but sold only to station employees.  A greenhouse with Tibetan prayer flags.  A laundry room where everyone can wash their clothes once a week. The shower allowance is three minutes twice a week.  Because the station is a government facility, there’s no smoking allowed indoors. Smoking areas are located outside and equipped with ashtrays.  People step out to smoke wearing just a T-shirt. Hey, it’s warm out.  The station has a U.S. post office. A couple dozen rubber stamps are laid out on the shelf: everyone can stamp their postcard or passport with whatever suits their fancy. For some completely inexplicable reason, tourists can’t mail a postcard from here. Only station staff. This is the first U.S. post office in the world with a discriminatory policy against senders. Would it kill them to mail an extra ten grams? A total mystery.  The station has Internet access, but visitors aren’t given the Wi-Fi password. Which means I won’t be able to check in on Foursquare. The station is bustling with activity: people are constantly unloading and moving things, melting water, zipping around on snowmobiles, and so forth.  From here, every direction is north.  But I’m interested in the South Pole itself. I didn’t come here to see the station, after all. What awaited me was something halfway between revelation and disappointment. It turns out that the reflective sphere, which I consider to be one of the most brilliant objects that exist to designate a landmark, is called the “Ceremonial Pole.” The Geographic South Pole is actually located a few hundred meters away.  The reflective sphere turned out to be dented. Nevertheless, no one can resist the temptation to photograph their reflection.  The sphere rests atop an uneven wooden post with a rather shoddy paint job.  This place is called the Ceremonial South Pole. This is where everyone takes photos and where the flags of the 12 countries studying Antarctica are located.  The Geographic South Pole is practically invisible at first glance. It’s the stick behind the white sign. The Americans evidently wanted to kill two birds with one stone: to have only their own flag at the actual Pole, and to make sure no one else got offended. So all the different flags got put up in another place, where the photogenic sphere is, and only the Stars and Stripes remained here. Although technically it’s the Norwegian flag that belongs on this spot.  The Geographic South Pole. The South Magnetic Pole, by the way, is located approximately eight hundred kilometers away from here, so there’s no point in trying to make your compass go nuts.  The knob at the top of the stick is replaced with a new one every year. It’s a tradition. The previous ones can be viewed in a display case at the station.  The Pole.  You’ve got to leave your mark on this earth somehow—so I moved the Geographic Pole three centimeters to the north. Don’t forget to update your maps!  It’s time to fly back.  Antarctica.  Our campsite.  The weather was so accommodating that we managed to squeeze everything into two days, although we’d originally planned to spend an entire week here. Since no one wanted to waste another five days being bored to death in a tent with bad food, we asked to be taken on the next Ilyushin Il-76 cargo flight back. As luck would have it, the plane was due to return the next morning. Here it comes.  This turned out to be the crew’s hundredth landing on Antarctica. The camp’s staff dressed up as cows and leopards, put on horns and tails, wrote “You’re the best!” on a bed sheet in Russian, and greeted the anniversary landing with full fanfare.  Visiting the South Pole—check!  |