PitcairnMap

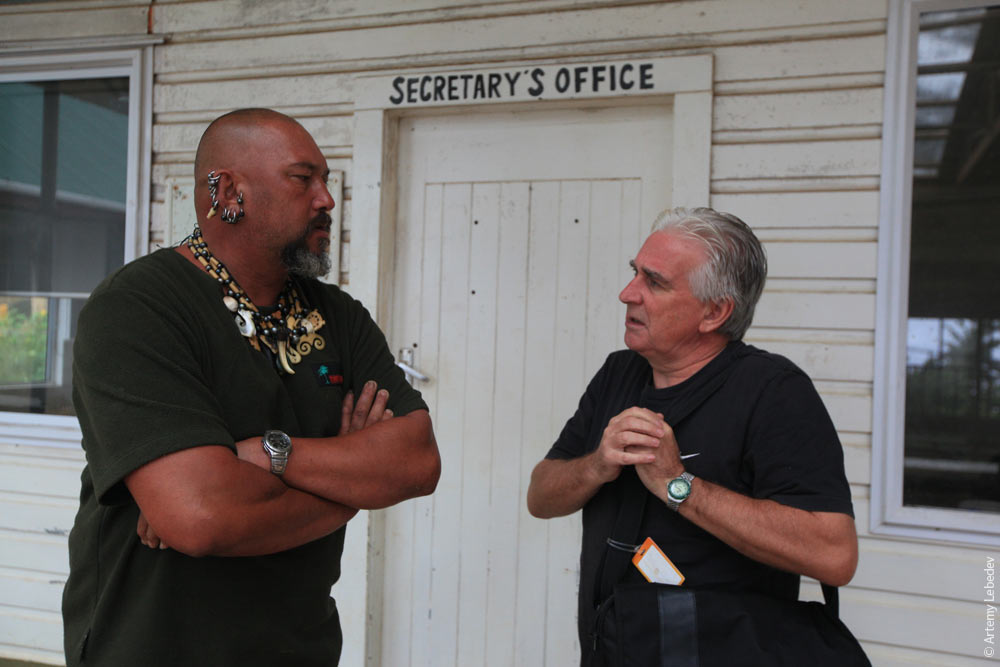

September The length of the historical preface to this state is inversely proportional to its size.  It all began in 1787, when the British government dispatched an expedition to Tahiti to collect some breadfruit tree saplings. The idea was to transplant the breadfruit tree to the Caribbean, where it could be used as a cheap source of food for slaves—since there were a lot of slaves there and not a lot of cheap food. The Royal Navy bought a ship, renamed it to Bounty, appointed William Bligh as captain and sent it on its mission.  Bligh set course past Tierra del Fuego, but the storms there were so bad (I even had my glasses blown off into the sea in Chile) that, after a month of torture, he decided to try and sail to his destination from the opposite side—through what is now known as the Southern Ocean. They made it to Tahiti, but by then the crew was so tired that they stayed put for six months. In that time, the ship’s company managed to not only collect the breadfruit saplings, but to make friends with the local ladies as well. It was hard to leave. But there was business to attend to, so they set sail.  They hadn’t gotten very far when mutiny— instigated by the master’s mate, Fletcher Christian—broke out on the ship. The mutiny was bloodless but still no joke. Captain Bligh and his loyal followers were set adrift in a small launch with a bare minimum of water and provisions. Bligh was doomed.  Christian and the remaining sailors on the Bounty sailed back to Tahiti. The mutineers dreamed wistfully of the Tahitian women. They made it back, found their ladies, and resumed having a good time. But Christian knew that sooner or later the vengeful sword of British justice would catch up with them, and then they’d really be in for it. So he decided it was time to split. Seven more of the crew members joined him. Each took along a Polynesian woman. They also brought six natives as slaves and three more women for them, too.  Jumping ahead, I can tell you that the sailors who stayed on Tahiti were eventually taken back to England, where they were all tried and some even executed. Fletcher, meanwhile, went to seek the uninhabited island of Pitcairn, which he saw marked on the map. The island had been discovered not long before the events in question and was named after the sailor who first spotted it. But the location indicated on the map was 200 miles off, so it was a while before they found it. The year was 1790.  Our mutineers began to live happily ever after. They figured out how to distill alcohol, so good times were had by all. The island was divided up by the Englishmen, who left nothing for their Polynesian friends. The ship was stripped of everything valuable and then burned.  And so they lived until, one fine day, the wife of one of the Englishmen fell of a cliff while collecting birds’ eggs (or so the story goes). The guy grieved for a little while and then went to take one of the chicks away from the six Polynesians. Let me remind you that the aborigines had three chicks to share among six dudes as it was. Hardly pleased with this turn of events, they decided to bump off all the white guys. They succeeded in killing half of them (including Fletcher); the remaining half killed all the Polynesians. As a result of natural attrition due to drinking and knife-fights, there eventually remained a bunch of women, even more children (since a fair number had been born by that point) and one single dude—John Adams.  And then came the moment of enlightenment. The Scriptures played a part: Adams somehow started reading the Bible, got into it and began to educate the women and children. Righteousness and order ensued.  Thirty-five years later, a British ship happened to be sailing past the island. Its captain listened with much astonishment to the story told by the gray-bearded old man who stood surrounded by a crowd of swarthy villagers. Adams was granted amnesty by the Crown. * * * Two hundred years have since gone by. All sorts of stuff happened in that time. At one point all of Pitcairn’s residents were resettled to the Norfolk Island and Pitcairn stood completely uninhabited for a couple of years. But some of the families came back. And today the island is still populated by direct descendants of the Bounty mutineers, with some Polynesian blood mixed in.  It’s impossible to get close to the island on a large ship. All cargo and passengers are brought over on launches, which are stored in a garage.  The ocean is always choppy here.  Until recently, wooden boats were manufactured right here on the island, but today they’ve been replaced with aluminum ones. The last local model, made in 1980, stands on the shore like a museum piece.  The launch approaches the anchored ship. Aboard it are several able-bodied men and a policewoman.  A stamp in the passport—and onto to the island. About 50 people live here.  There are no hotels on Pitcairn. My gracious hosts are Betty and Tom Christian. Tom is the many-times-great-grandson of the very Christian who started the mutiny. Betty shows me around the island.  Her responsibilities also include monitoring the weather station and reporting the data to New Zealand. Betty takes a reading.  Every day, she also replaces the card in the sunshine recorder (a special device for measuring the amount of sunlight). When the sun is not obscured by clouds, its rays pass through the glass orb and burn a hole in the card. The result is a visual record of the sun’s activity throughout the day. The sun hours are added up and then reported to the New Zealand MetService.  Everyone on the island has several professions and occupations. Betty, for instance, also has a café, which opens its doors once every couple of months—whenever she feels like it. There’s also another café owned by a different family with the same name. It’s open on Fridays. This Friday, patrons have a choice of chicken or fish; half the country has reserved a table.  The bartender at Christian’s Café also has a day job as the country’s treasurer.

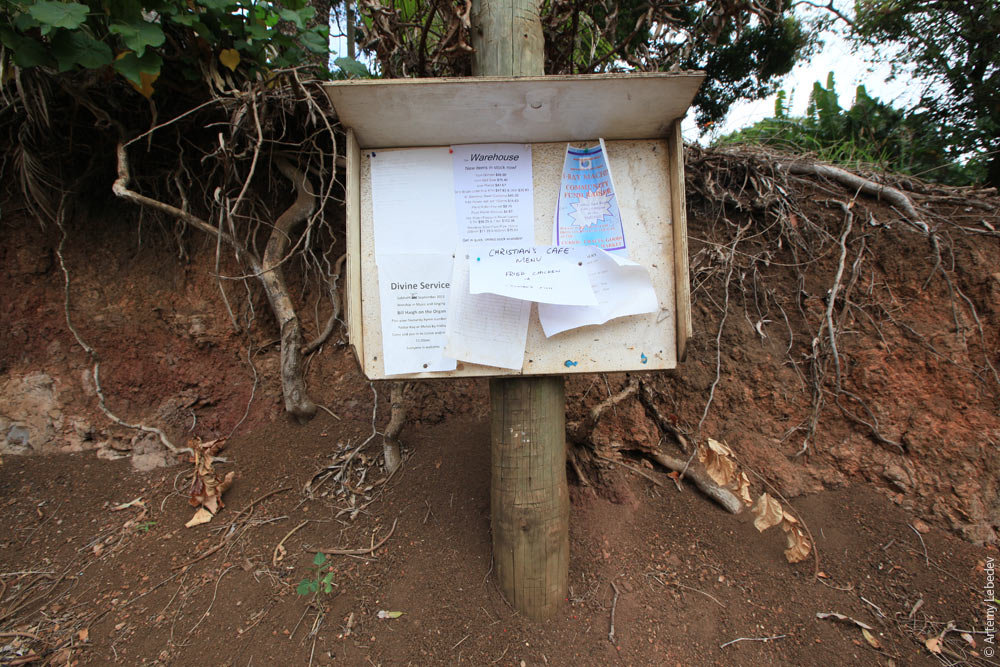

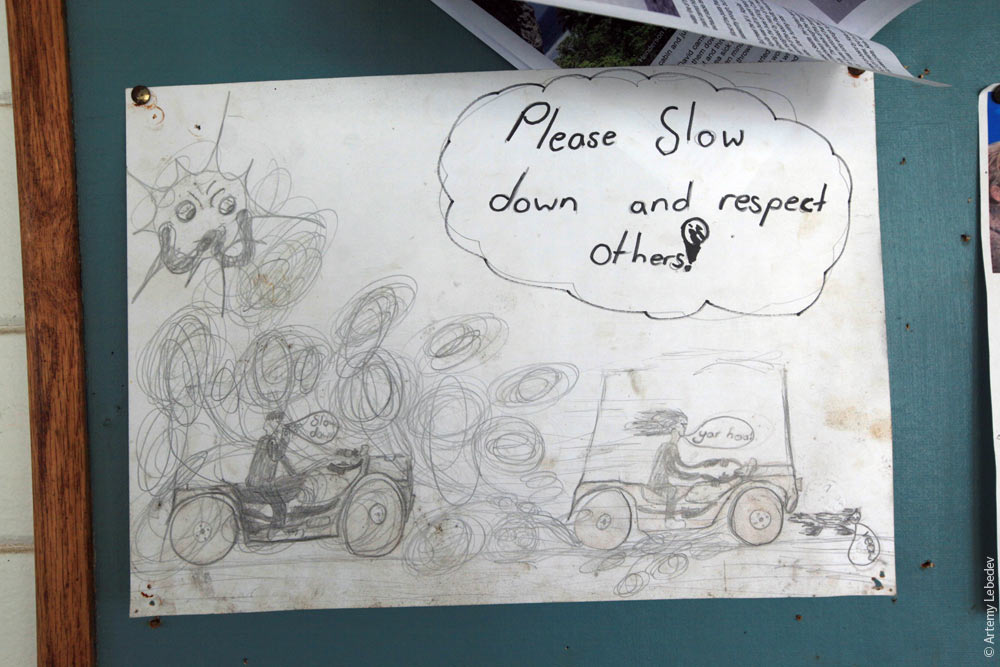

By the way, a couple of my fellow countrymen left a  Dmitry Malov, Yulia Vlasova 24.02.2011 The one and only settlement on the island is called Adamstown.  There’s a health centre here.  And a post office. The bulk of Pitcairn’s revenue once came from the sale of its stamps. Today, stamp collectors have all but gone extinct.  The post office is located in the central square. The square has a hopscotch court drawn on the ground.  There’s a grill on one side of the square; the Bounty’s anchor is on the other.  On the grill side is a church where everyone gathers on Saturdays. At the end of the 19th century, a missionary came here and converted everyone to Seventh Day Adventism. The church hosts Bible discussions followed by karaoke songs about Jesus. A system administrator who has come here to configure something plays the electric organ.  A public toilet and a trash can.  The only trash dump in the country. Once the pit is full, the trash is burned, the hole is filled and a new one is dug.  There’s a severe shortage of fresh water on the island. The stream has run dry, so everyone relies solely on collected rainwater. Every flush of the toilet is accompanied by a pang of guilt.  The Pitcairn General Store. Shipments come in four times a year. Yet the store even has cat food on the shelves.  Everyone used to get around the island on foot, but eventually progress, the advances of civilization and laziness made their way here as well: today the main mode of transportation is the quad bike. One family even has a car.  Policewoman Brenda Christian takes the children home.  There are two “Slow Down” signs on the island.  And one speed camera. It consists of a point-and-shoot body nailed to a sign.  But even the old ladies speed.  Every house has a two-way radio. These are used for important communications.  Imagine everyone sitting down at dinner. Suddenly, a female voice comes on the radio: “Attention, attention! This is a public announcement. Please don’t speed when driving your quad bikes, particularly when entering the main road from a side road. Also, please do not pick bananas that don’t belong to you. Thank you.”  A huge scandal broke out here in 2004, when reports surfaced that sex with minors was a common occurrence on the island. An investigation began, its findings were shocking. Judges and prosecutors arrived on the island, the trial lasted several years, a quarter of the working-age population was convicted and put in the jail which had to be built specifically for this purpose. The whole thing cost a ton of money, but the law is the law. An independent policeman was appointed to the island from New Zealand to reinforce the law. But there are practically no children on the island today—only the aging population. And an empty jail. Any mention of the jail and the sexual assault trial seems to have a rather strange effect on the citizens of Pitcairn, so it’s best not to bring the subject up. There aren’t even any signs to the jail.  And whatever became of Captain William Bligh, whom the mutineers sent off to a certain death in the open waters? Together with his loyal men, he traveled 6700 kilometers, reached Timor, then made his way back to England and lived another 28 years successfully serving the Royal Navy. His tomb in London is adorned with a breadfruit. |