South Korea. Part I. Ten thousand phenomenaMapApril 27 — May 3, 2007 The South Korean border control official studied my North Korean visa with great interest. He enquired whether I really had been over there. Then he smiled as if I’d told him that his granddad’s cousin, who he hadn’t seen for 50 years, says hi. The only bit of material culture that’s the same as in North Korea (aside from the shape of the roofs on traditional houses), — is the slit in the cashier’s window, which is a pain to use. To be fair, I only saw it once — right where South Koreans let you take a look at their northern neighbours.  Everyone asked me whether I’d been to Korea before. I replied that I had, to North Korea. I couldn’t quite figure out what they think about those who’ve travelled there. Some smile, others close up and cut the conversation short. North Koreans show foreigners a special earthwork, which looks like a green lawn from the south, while there are anti-tank gates on its north side. South Koreans take tourists down into a tunnel Northerners dug underneath the border. In other words, they’re both as bad as each other. The only difference being that here, if they say no photography or video recordings, they really mean it. In the bit overlooking the demilitarized zone you’re not allowed to take snaps beyond the yellow line. If you take a photograph past that line, a soldier will come up to you and delete the picture.  This is the view you get standing on that line:

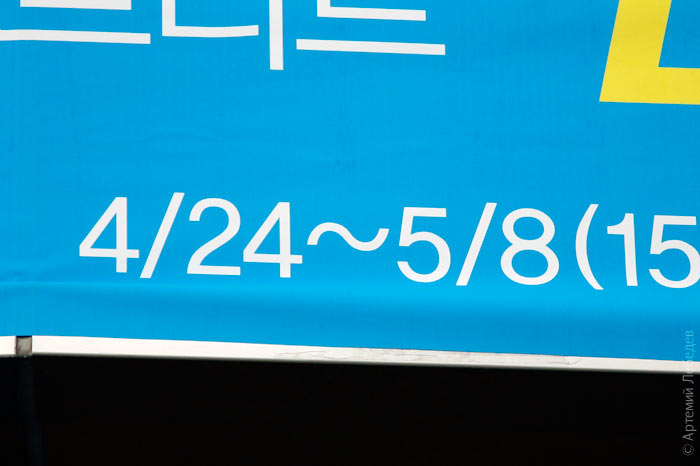

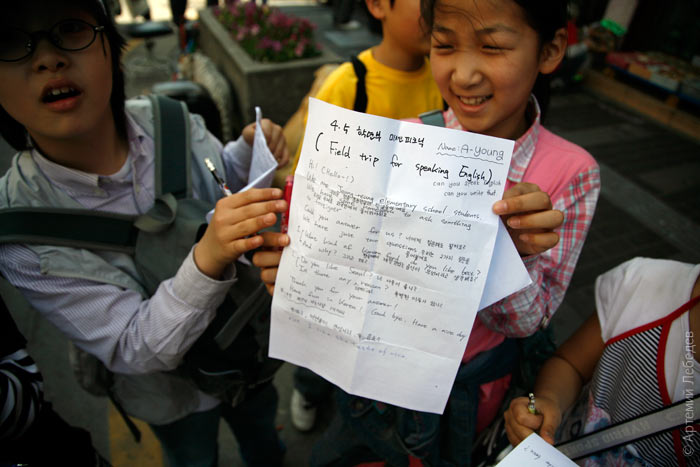

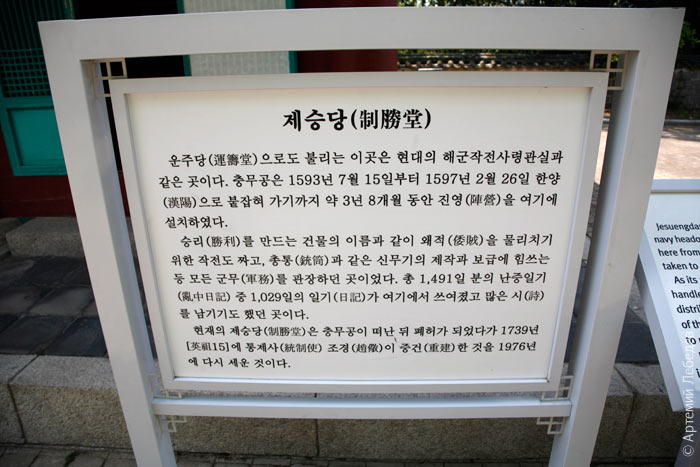

DPRK: Aside from that South Korea turned out to be a truly tremendous place. I got the impression that it’s even more interesting than Japan. The most ingenious bit of South Korean culture is the range symbol — a squiggly line. Our long dash pales in comparison to the ~. Range signs can be found in any hotchpotch of signs. Here it’s been used to mean “between 24 April and 8 May”:  In this instance it means “no entry between 10am and 10pm”. Note that the sign also works vertically, displaying remarkable powers of versatility.  The electronics trade here is one of the dullest sights on this earth. Identical counters are decorated with lab flasks full of energy-saving light bulbs. That’s it.  On the bright side, the utility pole wires are some of the most poetic in the world.  Hardly anyone speaks English here. I was approached in the street by a gaggle of children who started chanting “Hello! We are students from the national Yon-ryon school and we have to ask a foreigner a few questions”. They had two questions: what Korean food do I like and do I like Seoul.  I was standing there, looking at a map of the city, when a second gaggle approached, the exact same questions at the ready. I quickly answered them and then fled that street to avoid spending the rest of my day conversing with the entire school.  On this street people were playing games.  On the third street there was a disabled man wearing pieces of car tire inner tubes on his leg stumps. I saw something similar several times, but I still don’t get what the point is — to add length and girth, or to arouse greater pity.  This place is bustling round-the-clock. The main method of advertising is to have a girl stand outside your store and loudly beckon customers to come in, repeating the same slogans over and over. Sometimes shop entrances are just two metres apart, so the girls have to both outshout and ignore each other.  The food safety authorities would be appalled if they saw the street food trade here; Koreans have gotten over it somehow. There are queues roughly fifty people long to buy certain types of food (it’s either dirt cheap, or downright delicious — I didn’t find out which). Mountains of waste pile up on and in all of the stalls and tents — for example, on this counter where they sell meat skewers:  I was on the verge of concluding that all of the food here is fit for consumption by Europeans when I suddenly happened upon some repulsive, pimply, wart-covered leeches, the size of a respectable cucumber. They squirmed as they waited for a foodie to stroll by.  If you’re apprehensive, there is a solution — opt for establishments bearing an official “good restaurant” sign.  Playgrounds are easy to recognise thanks to their familiar domes:  By the way, almost a third of Korea’s population is Christian (more or less evenly split between Catholics and Protestants):  The first thing you notice in any city is the crosses on the spires.  At nighttime they’re lit up with neon lights.  Buddhist temples are much more modest, both in appearance and number. That being said, no one bats an eyelid at the swastika decoration in this fence.  It might seem like Koreans use characters, but in fact they have their own, relatively small, alphabet. Although, truth be told, sometimes there aren’t enough synonyms, in which case they write the word in brackets using Chinese characters to make it easier to understand what exactly they’re talking about.  No one is ill at ease if they see someone peeing, so urinals are visible from the street.  Public soap is impaled on a spike; you can rub your hands against it.  They take good care of state property here. Even old electrical cabinets containing traffic light equipment are all mounted on concrete platforms, so that if a car crashes into one the equipment will come out unscathed.  Poles are wrapped in special knobbly rubber tape to which ads won’t stick.  The postbox in profile looks like a bird.  Lampposts are the main form of street art. Nowhere else have I see such varied lamppost designs.  |