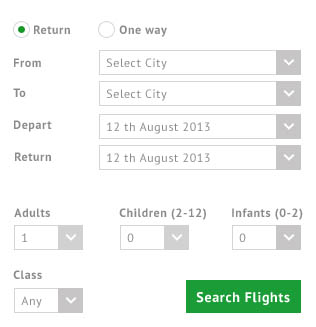

Turkmenistan. Part II. Main DetailsMapMay 26...31, 2014 The most interesting thing about Turkmenistan is that it’s impossible to get into. The fate of this former Soviet republic has been quite surprising. Russian citizens are denied entry 99% of the time. I’ve been trying to come here for ten years and received four visa denials in that time. With each denial, my desire to visit Turkmenistan only multiplied. And then, finally, a miracle happened.  Ordinary people don’t go to Turkmenistan. Because no one will let them. Turkmenistan is ten times more secretive than North Korea or Equatorial Guinea. There are practically no reports from here. At the same time, freedom of movement within the country is mostly unrestricted. A trip to Turkmenistan begins with a visit to the website of Turkmenistan Airlines, the country’s sole air carrier. The home page looks normal and up to date. It’ll make for a pretty screenshot. The only difference is that if you try to buy a ticket, you’ll be sorely disappointed. The search form is actually an image, with the date frozen at August 12, 2013 (anyone who wishes to see for themselves is welcome to do so—turkmenairlines.com). Here it is in its entirety:  Flights within the country are incredibly cheap. The catch is that you can’t just go and buy a ticket. Tickets from Ashgabat to Turkmenbashi officially cost $25, but you can only get one if you pay $50 through the right person. And since knowing the right people and online sales are incompatible, the website doesn’t work. The extra fee must be presented in person to your friends at the ticket office. Turkmenistan is an odd mix of Stalinism, the Juche Idea, Brezhnev Stagnation communism and endearing Asian hospitality. I love studying the fates of rulers who got whacked over the head by life. For instance, the Cambodian Pol Pot studied at the Sorbonne, but got kicked out for poor grades. So he returned to his homeland, rose to power and got his revenge for everything. City residents were evacuated to the countryside to grow rice. Everyone who showed any sign of being educated (such as wearing glasses) was sent off for “re-education.” The only people who survived were either truly backward peasants or those who managed to pass themselves off as such in time. Teachers, doctors, construction workers—the reprisals affected everyone. It took just four years for the country to return to the Stone Age. The story of the Turkmen people is somewhat similar, only minus the bloodshed. President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov lost his mother and brothers during a terrible earthquake in Ashgabat in 1948. He was sent to an orphanage, then to study in Leningrad. Once there, he decided to get revenge on his own people for the fact that not a single relative had taken him in to raise him (which actually goes against the tenets of Islamic cultures, where there are no orphanages). He joined the Komsomol and the Communist Party, became a prominent party functionary, returned to the Turkmen SSR, became Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, and then, after the collapse of the USSR, appointed himself President for Life. That’s when Saparmurat really took it out on his people. He outlawed whistling, gold teeth, libraries, rural hospitals, opera and ballet, made everyone study his book Ruhnama, erected a bunch of gold monuments to himself and generally raged until his very death, taking advantage of the country’s plentiful natural gas resources, which brought in a steady stream of foreign currency. To prevent anyone from criticizing this idiocy, he preemptively restricted entry into the country. Nowadays, there’s Internet access, but LiveJournal, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and several other questionable websites are banned.  Life is fairly peaceful here these days. No one is having their gold teeth forcibly pulled out:  The new president loosened the cult of personality and abolished many of the stupid restrictions. But that doesn’t mean a business has the right not to hang a portrait of the president over a rug in its office. The portrait and rug behind it are mandatory.  The context is completely irrelevant. Rug first, presidential portrait second. It doesn’t matter if it’s right next to a TV blasting the Russian channel TNT (which is very popular in Turkmenistan) with its dirty jokes all day long.  Whereas in Russia a rug is a measure of mockery, in Turkmenistan it’s a measure of respect.  Of course, it’s not always possible to hang a rug everywhere. On a plane, a portrait of the president counts as a sufficient token of respect, even without the rug.  But if space allows, the rug is mandatory.  The administration sends out a daily photo of the president to all the newspapers for publication on the front page. The two newspapers at the top are from today. That’s why they have the same photo of the president. The photos of the president below them are different because those are newspapers from other days.  Falling rocks are symbolized by neatly spherical stones.  In terms of men’s clothing, anything goes here, but the women wear traditional garments.  The ones in red are university students.  The ones in green are schoolgirls. All young women protect themselves from the sun with umbrellas during the day. While we’re on the topic of women, it’s worth mentioning that women’s graves are dug one shovelful deeper than men’s—so that they remain below men even after death!  Tall swings are an important attribute of the Feast of the Sacrifice in Turkmenistan. They’re only used once a year, the rest of the time they’re wrapped up to prevent fooling around. Swinging on these swings absolves you of your sins.  The most interesting detail, one that deserves to be spread worldwide, is the tradition of stretching ribbons from the tops of buildings to the ground. It’s simple, festive and very pretty.  If there’s no building nearby, a lamppost will do. Ribbons stretched down from one look fantastic as well.  Watch out for camels.  Indeed, there they are.  Desert highways are lined with curious enclosures: woven rectangular corrals. They catch the sand, so the road stays clean for a long time.  The cars and trucks are mostly prehistoric.  There’s a ban on importing foreign cars with engines over 3.5 liters (even for foreign embassies).  Talking on the phone while driving is prohibited. Driving a dirty car is prohibited—there are patrols on the lookout for offenders after every rainfall. Importing cars with tinted windows is absolutely prohibited, but there’s no law against tinting the windows once the car is inside the country.  In other words, the rules don’t always make sense.  And the cars in use here are something you’d be hard-pressed to find in a museum anywhere else.  100 liters of gas cost $22. Every citizen with a car is entitled to 720 liters of free gas every six months.  Turkmens don’t like to buckle up, but the police like to give drivers a hard time. The solution? Most attach their seatbelt to the hand brake.  Water is free in the country. You could open your tap and let it run forever if you felt like it. Household gas bills come to a couple of dollars a year. The people are happy. Electricity will run about $40 a year for a three-bedroom apartment. That’s why the lights are always on everywhere. No one can be bothered to go turn off the light switch. Smoking in public is prohibited. All the cafés, restaurants and clubs in the country close at 11 p.m. Everyone should be home after 11. If you’re unmarried, it’s better to be home by 10. An old man, upon learning that I intended to travel across the country, told me, “It’s so beautiful—you’re going to run out of memory on your camera!”  Those who are allowed into the country must surely run out of memory on their cameras. |