ScotlandMapOctober 17–20, 2008 The Moscow advertising agency in charge of Grant’s whisky came up with an artistic campaign that involved asking five creative professionals to don a different hat and take a series of photographs. I was given the genre of advertising photography, a plane ticket, a hotel address, and three bottles of whisky that I left behind in Moscow. GirvanMapThis is where the Grant’s distillery is located. It was originally built here because of the nearby lake, which provided free water. Then a tax was introduced on the water, but the distillery had already been built. And so it continues to operate here to this day. Despite having a view of the sea, the facilities are utterly bleak and industrial. What’s more, there’s hardly anyone here—everything is automated.  The whisky barrels stacked amidst the mud might have been marginally serviceable as a backdrop, but for an advertising photo this was all decidedly wrong.  Very few people in general find their way to this small, quiet Scottish town.  Everything is laid-back and slow. Traffic signs are weighed down with sandbags so that they don’t get blown over.  There are “Elderly people” everywhere.  The supermarket has charity bins for second-hand items standing outside. You can donate your shoes and clothes to the needy.  Although Grant’s whisky is produced a kilometer away from here, the supermarket doesn’t carry it. I need to take an advertising photo, but I don’t have a bottle. The distillery doesn’t have any either—the whisky is bottled somewhere else. The supermarket itself has a wonderful self-checkout station. Customers scan their items themselves, put their card or cash into the machine, bag their groceries and go home. Everything is built on honesty.  Sinks in Britain don’t have mixer taps. Instead, they have two separate taps, one for hot water and one for cold. Theoretically, you’re supposed to plug the sink and fill it until you get the water amount and temperature you need. Then you wash up in this soapy muck, drain the sink and rinse it after yourself. It’s horrid, but such is the tradition. And in public places, you don’t even get a stopper.  I check into my hotel. My room has a view of the rugged Scottish sea and Ailsa Craig—the island where the granite for curling stones comes from. Rock from other places simply won’t do for curling. The island even looks like a curling stone—all it’s missing is the handle.  The first thing the proprietor of my B&B asked me when she found out I was from Russia was, “Are you interested in variag? I asked her to repeat this unfamiliar English word several times, trying to get past her difficult Scottish accent. Turns out, she was talking about the wreckage of the Varyag cruiser, which is lying at the bottom of the sea six miles away from here. The locals have already gotten used to the fact that this is the only reason Russians come to Girvan. Apparently, several years ago a television crew from a major Russian station figured out that this was, in fact, the final resting place of the historic ship. I called a cab to go see the monument that was erected near the cruiser’s location. The taxi driver immediately offered to swing over and pick up his friend, who knows a lot about the Varyag. “People catch up to forty lobsters at a time in her boilers!” Bill Prince, an old sailor, told me. He had fished near the ship’s wreckage his entire life—but had no idea that this wreckage was somehow special.  Upon closer inspection, the story of the Varyag turned out to be quite interesting. Nicholas II contracted the Americans to build the cruiser in 1898. A year later, she was launched and commissioned into the Russian Navy. In 1904, the cruiser was stationed in Korea’s Chemulpo Bay, along with several Japanese, British and French ships. Suddenly the Russo-Japanese War broke out. The Japanese offered our guys a chance to surrender, but they refused and decided to try and escape. Fifteen Japanese battleships opened fire on the Varyag. The other states’ ships were observing neutrality and couldn’t do anything. The crew acted heroically in battle, thus earning its fame. A hundred and thirty people died out of nearly six hundred. The captain scuttled the cruiser so that she wouldn’t fall into the enemy’s hands. The survivors were transferred to the neutral vessels and sent back home. A couple of weeks later, the German magazine Jugend published a poem by Rudolf Greinz (translation by A. Owie):

All hands on deck, shipmates, all hands on deck! ...

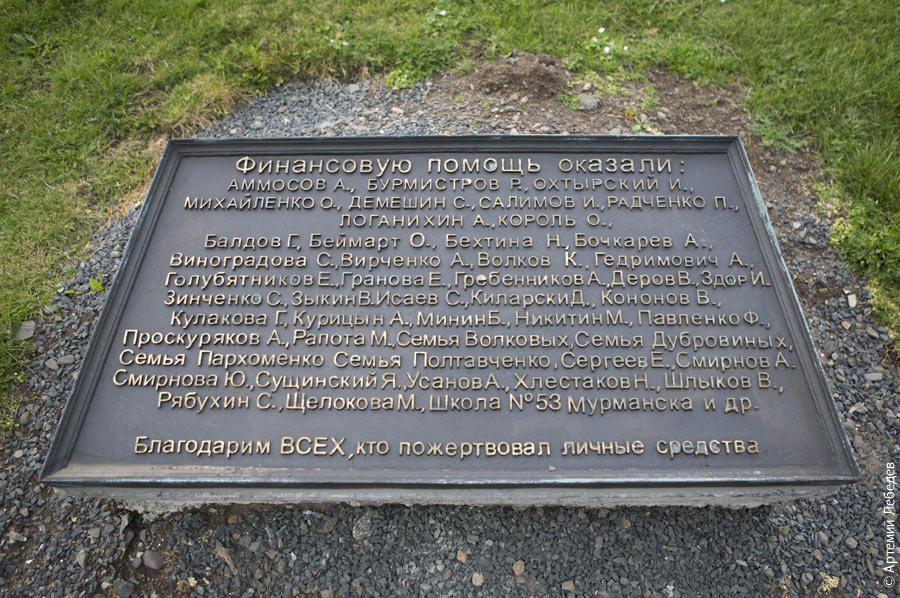

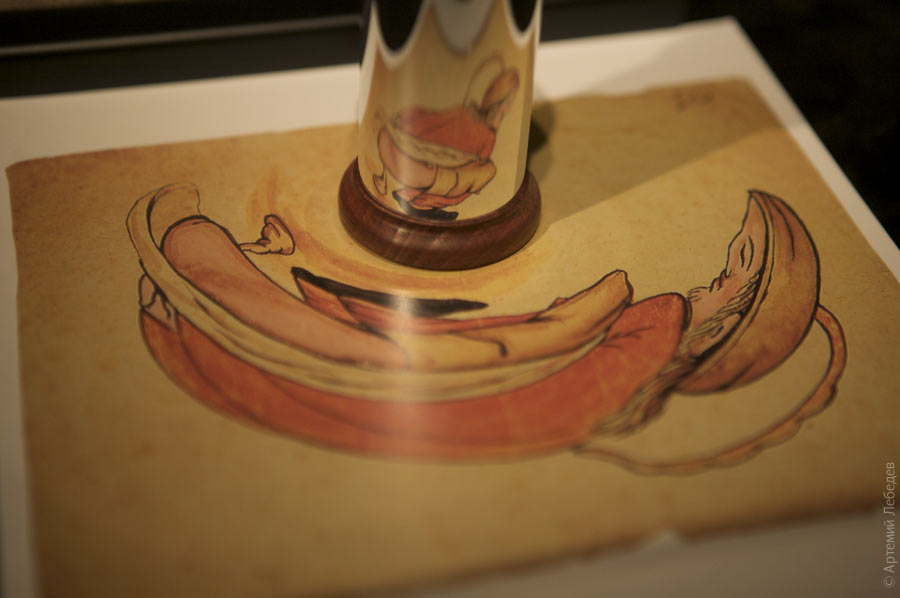

The sea waves will only forever bring fame The heroism ends there. Today, it’s the cruiser’s merits that are celebrated, not the nobly insane principles of the captain who refused to surrender or the crew’s courage in battle. A year later, the Japanese hoisted the cruiser up from the sea floor. Interestingly enough, the recovered personal belongings of the captain were sent back to him in Russia. The cruiser was renamed Soya and used as a training vessel. Then World War I broke out. Japan, now Russia’s ally, sold the former Varyag back to us as a token of friendship. In 1916, the ship’s former name was restored. Just a year later, however, she was sent off to Britain for repairs. Then the revolution happened, and the British seized the cruiser in compensation for the tsarist government’s outstanding debts. In 1920 the cruiser, which had become completely unserviceable by that point, was sold to the Germans for scrap. As she was being towed to Germany for demolition, the Varyag ran aground near Girvan and was abandoned. The locals made off with whatever they could, and five years later the ship sank to the bottom of the sea, where she remains to this day, providing fishermen with a bounty of lobsters. Grateful descendants have installed an insipid monument here, accompanied by a masterpiece of a plaque on which the spaces and commas seem to have been distributed using a random number generator. In the process, they also set a new world record for overall hideousness of execution.  FUNDING CONTRIBUTED BY: AMMOSOV A., BURMISTROV R., OKHTYRSKY I., MIKHAILENKO O., DEMESHIN S.,SALIMOV I.,RADCHENKO P., LOGANIKHIN A.,KOROL O., BaldovG., Beymart O., Bekhtina N.,Bochkarev A., Vinogradova S.,Virchenko A.,Volkov K., Gedrimovich A., GolubyatnikovE.,GranovaE.,GrebennikovA.,DerovV., Zdor I. ZinchenkoS., Zykin V.Isaev S.,KilarskiD., Kononov V., Kulakova G. Kuritsin A.,MininB., NikitinM., PavlenkoF., Proskuryakov A.,Rapota M.,Volkov Family,Dubrovin Family, Parkhomenko Family Poltavchenko Family , SergeevE.,Smirnov A. Smirnova Y.,SuschinksyY.,UsanovA., KhlestakovN., Shlykov V., Ryabukhin S.,SchelokovaM.,Murmansk School No.53 and others. We thank EVERYONE who made personal contributions. There was nothing else to do in Girvan, so I went to Dufftown, home of the Glenfiddich distillery, which is also owned by Grant’s. They don’t use slashes in fractions on road signs here (but they do in the US).  The speed cameras that measure average speed are particularly evil. They’re set up at the beginning and end of a fixed road section. The cameras record the car’s plate number and wait for it to drive through the section. If the car does this too quickly, it means it was going above the speed limit. A traffic ticket arrives by mail in due course. Here it is, the perfect police state.  The road surface markings are beyond reproach all throughout Britain. You can drive just by following them alone. I particularly liked the green reflective markers on the parts of the road where you can make a turn.  DufftownMapA tiny town surrounded by whisky distilleries.  Tradition dictates that the chimney of a building where malting takes place must resemble a pagoda. One Scotsman did it that way once, and everyone else copied him.  The facilities here have a more traditional appearance, so they let visitors in for tours. The stillhouse with copper pot stills looks about the same as it did a hundred years ago.  It turned out that the 12-year-old whiskies I was supposed to advertise are produced specifically for Russia and other pretentious countries. There’s only one such bottle of whisky in all of Scotland—it’s marked “1 of 120” and belongs to Mr. N, the owner of the whole company. By this point, I’d finally hatched my idea for the advertising photo: I wanted to take portraits of distillers, storekeepers and coopers in the style of cheery Socialist Realist factory worker nonsense, but have them all cradling a bottle of whisky like a baby in their arms. The fact that everyone would get fired if the bottle broke or got filthy had a very positive impact on my subjects: they held the bottle in the gentlest way possible. Everyone was holding a piece of foil behind the bottle to give it a nice warm glow in their hands. Here’s the forklift operator in the stockroom:  EdinburghMapI first came here in the fall of 2000. Back then, I thought that Edinburgh was the best city in the world. Eight years later, I’m not so sure of this anymore, but the city is still infinitely interesting and enjoyable.  Visiting the Camera Obscura next to the castle is a must. It’s been operating for over a hundred years and continues to delight to this day.  The same building also houses a museum of optical illusions. Here, you can learn how distinguished audiences of the 19th century entertained themselves. The image is deliberately distorted so that you can’t see what it depicts without a special reflective cylinder. But once you have the cylinder, everything immediately comes together.  Sorry, I got distracted. Edinburgh has all the components of an ideal city: old buildings, mountains and the sea. On top of that, it has a completely unique atmosphere and a huge number of pleasant oddities. For instance, the clock on the train station’s tower is always two and a half minutes ahead, so that fewer people miss their trains.  The city’s most amazing landmark is the National Monument commemorating the victory over Napoleon’s troops. They decided to build it next to the Nelson Monument (on the left behind the tree). The original plan was to construct an exact replica of the Parthenon in Athens. Twelve columns were built, after which the money for the monument ran out. Almost two hundred years have passed since then, and the ruins that resemble ruins continue to occupy the most prominent spot in the city. One can take pride in living near a monument like this.  AberdeenMapThey’ve installed new traffic lights with a curved pole here. The previous ones had a straight pole but were set further back into the sidewalk.  |