DubnaMap

April This is another nuclear research center; like Fryazino, it holds the status of “naukograd” (“science city”). It was here that Dubnium (Db), a chemical element with the atomic number 105, was first discovered. Although it’s not a closed city, it continues to successfully preserve many attributes of Soviet life.  Passenger elevator directions for use The city is situated on the banks of the Volga River.  Twenty-seat benches line the waterfront.  Although in reality it’s only 50 years old, no one can stop Dubna from claiming it’s older than Moscow and presenting this as a rock-solid fact.  From this place Dubna came into being. Founded by Yuri Dolgorukiy in 1134. There are 1960s lampposts everywhere.  Physics humor: the municipal pool is named after Archimedes.  International Conference Hall, Volga River Waterfront, Peace Recreational and Cultural Center, Archimedes Pool A Dubna trash can. There’s an unusually large (for a Russian city) number of cyclists here, by the way.  Bus stop signs are encased in exceptionally elaborate structures.  Bus shelters from the Soviet era continue to hold up despite the rust. While the structure on the right may also look like a bus shelter, it’s not. It’s a flyer bulletin board (there are many like it here).  Dubna has numerous four-story apartment buildings which strongly resemble the widespread Khrushchevka model, but were actually designed and built by the Bulgarians. Consequently, they’re referred to as Bulgarian here. One of their distinctive features is mail slots next to the front entrance.  Decorative balcony supports are something that Dubna has in common with closed nuclear cities (see Sarov, Zheleznogorsk, and Seversk). Here, however, municipal authorities began opposing architectural extravagances at a certain point in the city’s development, so the buildings on the block after this one lack these supports and the non-functional stuccowork on the façade. An illustrative example of the human eye’s need for extravagances.  Our tour of the city could have concluded there, since we’ve more or less seen everything interesting there is to see. But then I remembered that Dubna is home to the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR). The territory of the institute is surrounded with an electrified barbed wire fence and guarded by the military. But if you walk up to the gatehouse and convincingly tell the woman in camouflage, “I’m from CERN,” they’ll let you through. At JINR, you can see every existing apparatus that ends with “-tron” in a single day. Let’s begin with the Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions.

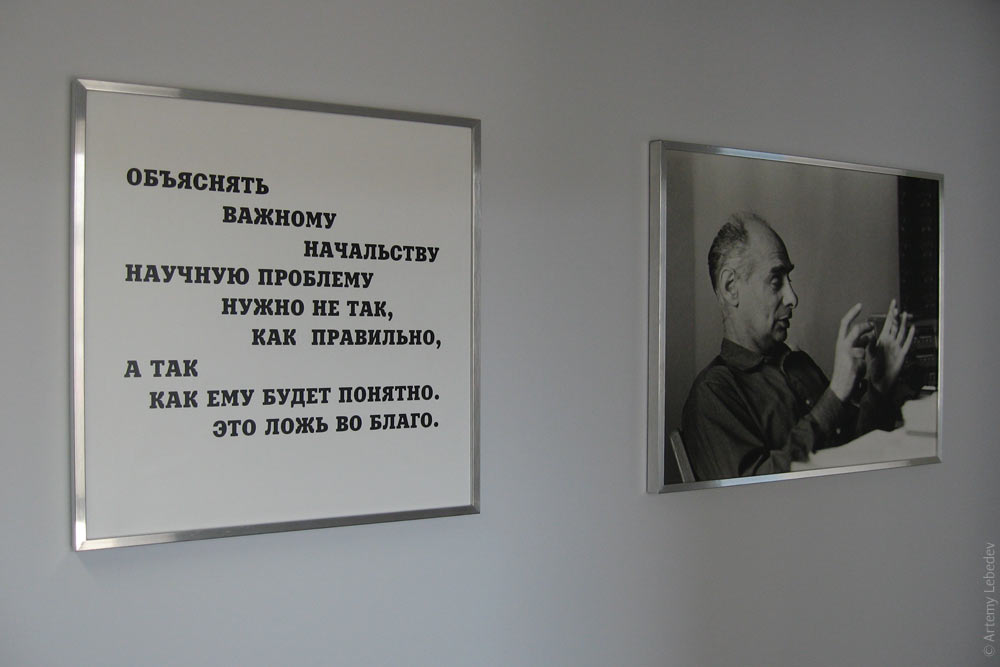

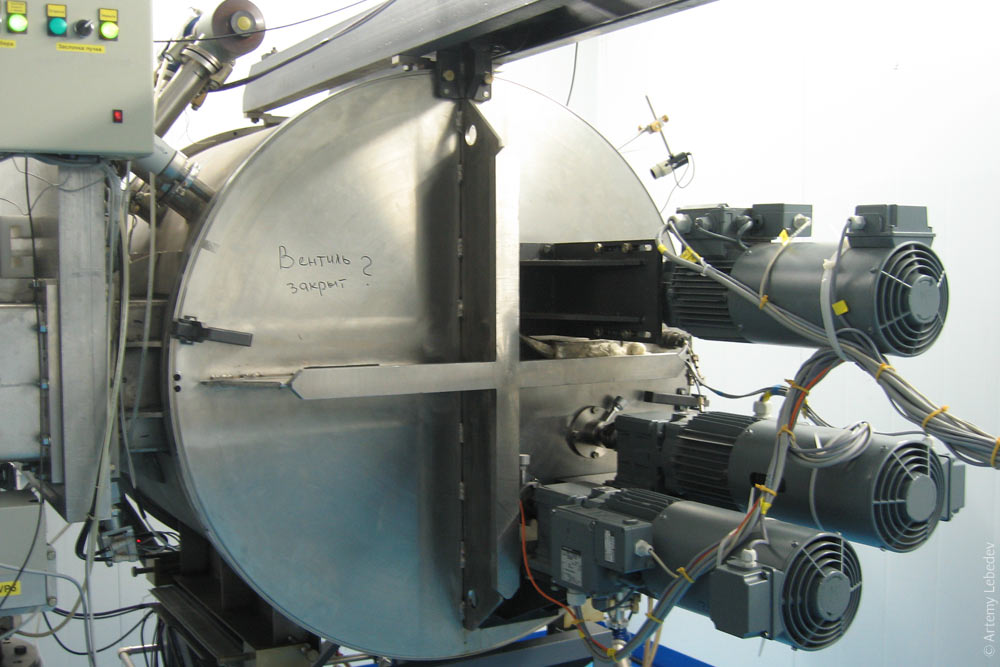

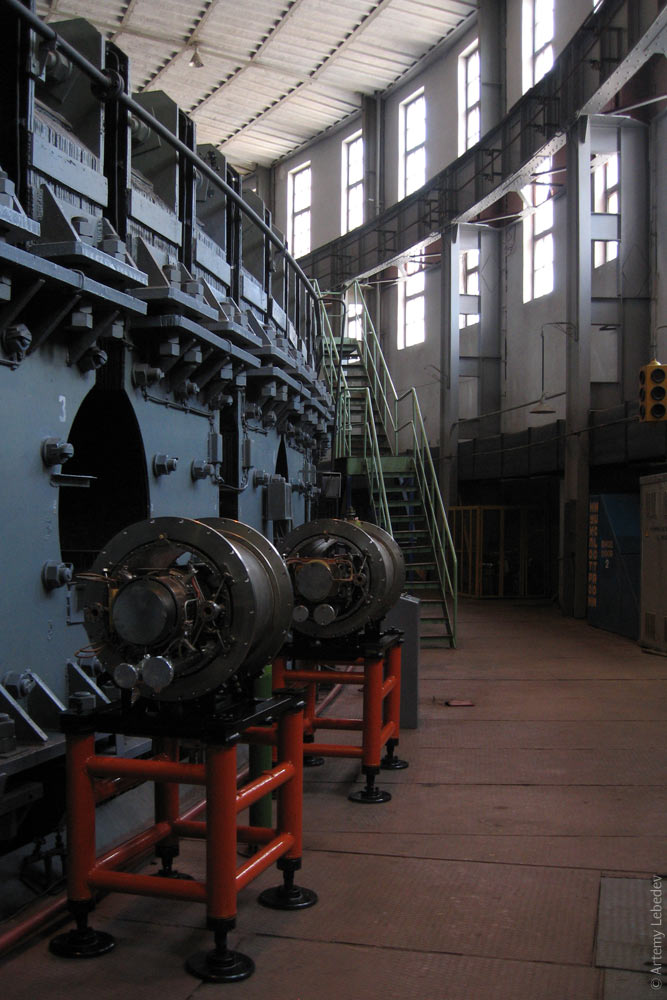

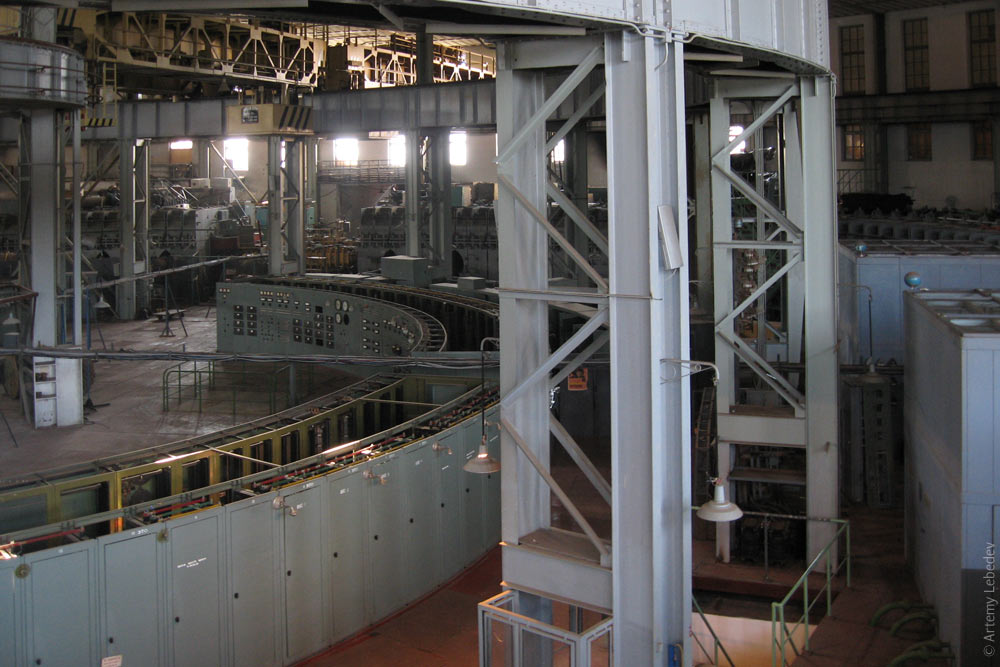

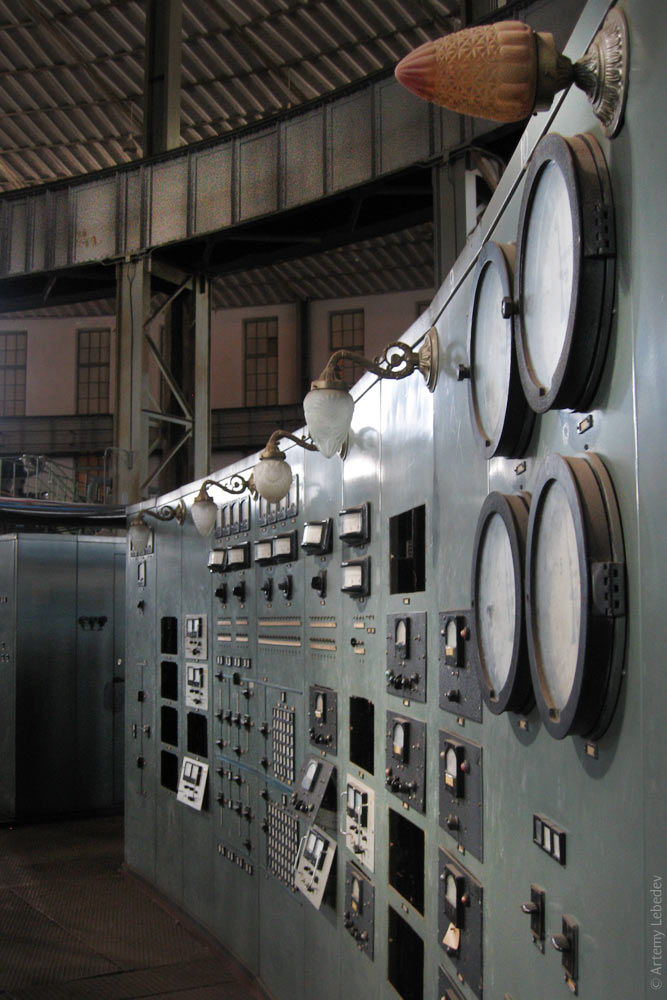

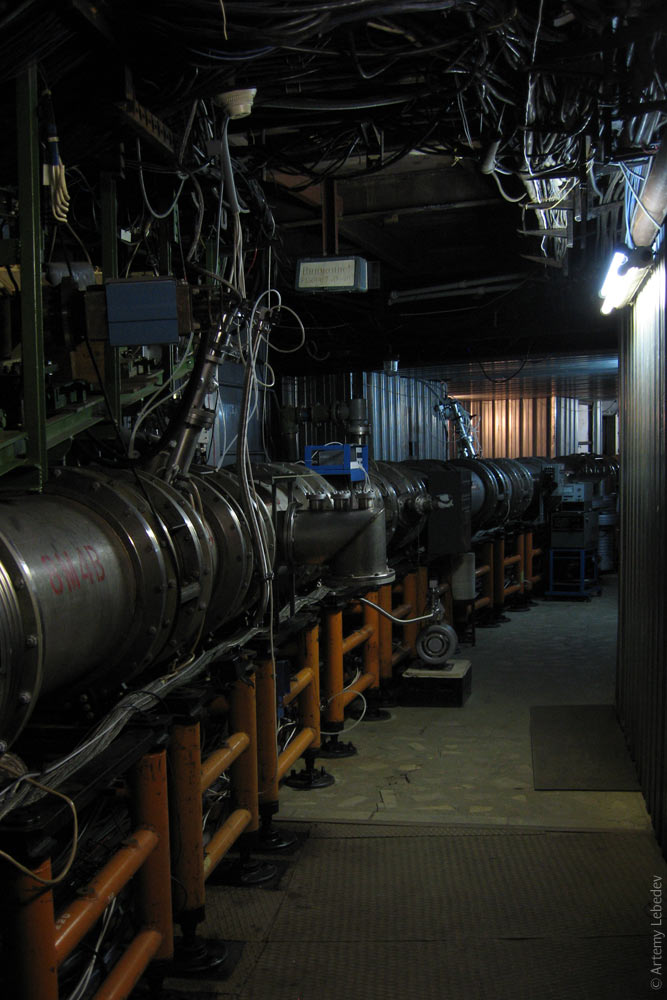

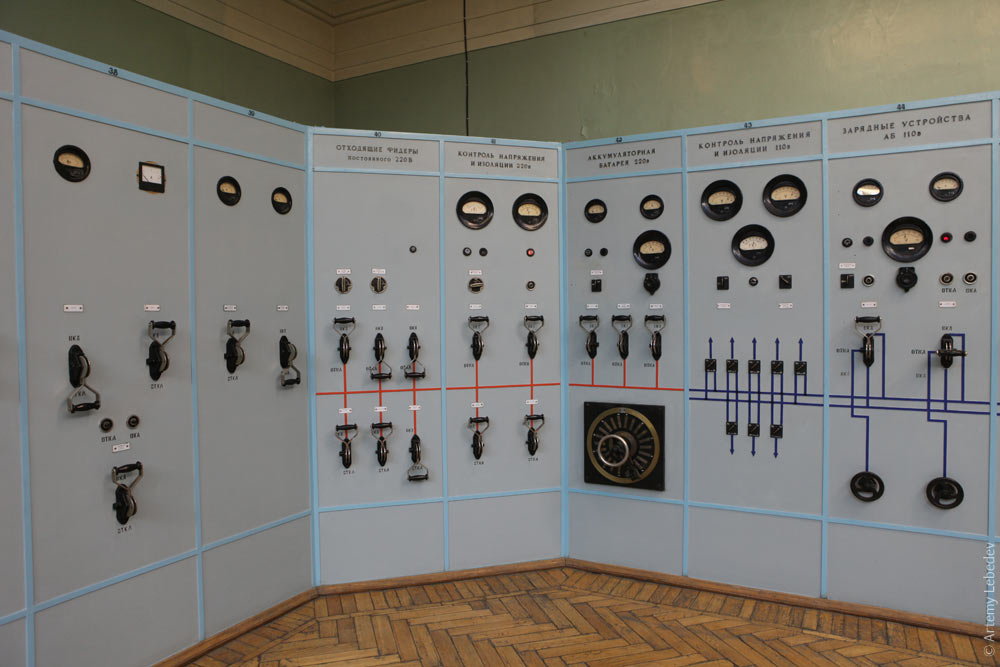

Scientific problems This is where the cyclotron is operated.  Cyclotron in operation Science in progress.  Valve closed? Metal shavings prettily await their scrap fate outside the lab.  A beautiful windowless building sits on the hill.  This is the phasotron. It’s old, but still works.  Phasotron From here you can cross over to the second part of the institute’s territory.  This is where the synchrophasotron is operated. Or rather, was operated up until five years ago. Now it’s being converted into something more useful.  Its size boggles the imagination.  But the sconces on the control console boggle the imagination even more. Here they are, the cutting-edge technologies of fifty years ago.  The basement of the synchrophasotron, previously filled with wires and cables, was cleared out to make room for a nuclotron. The entrance to it was evidently designed by someone specializing in Soviet arcade games.  The nuclotron. Pretty and useful.  The Moscow—Volga canal begins at Dubna. When the Volga was dammed to build the Ivankovo Hydro Power Plant, the Moscow Sea (also known as the Ivankovo Reservoir) was formed as a result. Two giant monuments were erected on its shores—one to Lenin and one to Stalin. Stalin was later blown up, but Lenin remains. Three folkloric characters can be seen boozing at his pedestal.  The road over the dam consists of a single reversible lane. This is where the two halves of the city connect. I never made it to the other side, but rumor has it that everything is completely different over there. The locals try to avoid driving to the opposite shore without need, because you end up standing at the light for half an hour every time.  The magic words to get you past security at the hydro power plant are, “I’m here to investigate a leak.” The plant was built in 1937 but continues to operate to this day and has simultaneously turned into a living museum. Everything here remains completely unchanged.  The turbine room contains equipment of unbelievable industrial beauty, manufactured by Stalin Leningrad Metal Works. Looking at all this, you realize that back in the 1930s, we were every bit as advanced as Britain or any other nation.  Every detail is a feast for the eyes.  Duplex Filter. Both On. Left On. Right On. Off A gorgeous mimic control panel. The square instrument in the top left corner of the photo is modern, everything else is from the 30s.  Outgoing Feeders DC 220 V, Voltage and Isolation Controls 220 V, Accumulator Battery 220 V, Voltage and Isolation Controls 110 V, Charging Equipment AB 110 V It’s really a shame that all the original legends were painted over. It looks a bit sparse without them. But the array of six panel meters and three light bulbs looks exactly like how the future was envisioned in the 30s.  Tempy—Vostochnaya Line 110 kV, Generator #1 The future caught Dubna by surprise.  |