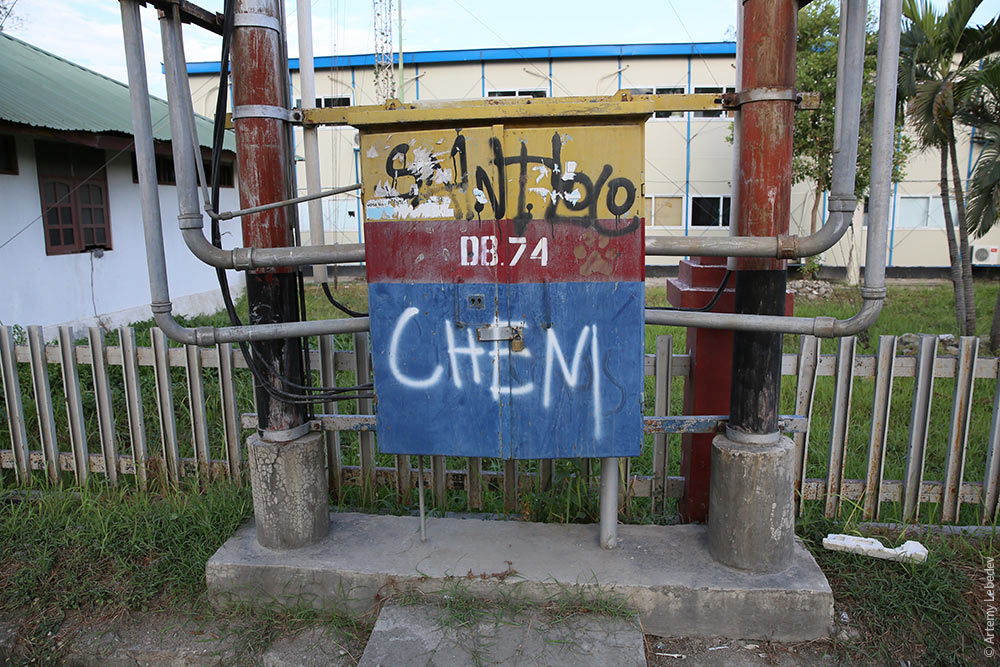

East TimorMapOctober 17–19, 2013 The country’s second official name is Timor-Leste. This name fully reflects the colonial history of this unfortunate land. “Timor” means “East” in Indonesian, and “Leste” means “East” in Portuguese. East Timor was a Portuguese colony until 1975. Nine days after gaining its independence, the country was occupied by Indonesian troops (speaking of good relations with mother countries). The Indonesians committed all sorts of atrocities here for a quarter of a century and killed a bunch of people. But the Timorese never accepted them as their new masters.  Finally, in 1999, a referendum was held, and the country’s residents voted in favor of independence. And then the most unexpected thing happened. In the three weeks that it took them to leave the country, Indonesian troops completely destroyed everything that could be destroyed, following the principle of “if I can’t have it, no one will.” They burned down all the homes, offices, schools, and hospitals; blew up the power stations and water canals, did unspeakable things. They would have probably reduced anything that was left to dust if not for Australia, which sent in peacekeeping forces and saved Timor from being wiped off the face of the earth. A smoking ruin without water or electricity, Timor began its path to recovery. Today it’s a reasonably normal single-story, poor, but optimistic Asian country.  DiliMapSome people might think this is the butthole of the world.  Parts of it fit the bill, of course.  But overall it’s quite all right. Certainly better than someplace like Juba.  The main street.  A new shopping mall, the largest and most modern one. Naturally, the entire outside is taken up by advertising.  Regular people buy everything on the street. Let’s see what’s for sale. Vegetables and greens.  Bananas of every conceivable length and girth.  Chicken.  Or fish.  Wealthy people fuel up at gas stations.  And regular folk buy gasoline in jugs from carts.  Fixed-run taxis won’t go anywhere until there are at least five passengers hanging from the driver-side door.  Traffic accident statistics.  Vehicle traffic lights have countdown timers on which the numbers slide downwards for some reason.  Pedestrian lights have an adorable animation.  A kilometer marker post.  A license plate.  Roundabout.  Boys and girls on “children” signs have the bottom of their legs sawed off. It didn’t fit in the template.  Church.  No firearms inside, please.  There are some payphone half-booths in the streets, but of course they’re all out of order.  Cables are fed into electrical boxes through pipes (reminds me of Pakistan somehow).  Utility poles are timidly protected from would-be climbers (like in Tel Aviv, Ankara, Jakarta, and Peru).  A trash can that has miraculously managed to survive. There are no trash cans in the city for the most part.  A rest stop.  A post office.  Timor’s main detail is a special roof shape that resembles a Kazakh or Kyrgyz hat.  I was lucky enough to catch a screening of the first-ever Timorese film, Beatriz’s War (I’ve already seen the first film out of Kaluga, Wet Firewood, and the first-ever Tuvan film, Kelin Kystyn Khomudaly). Here’s a summary of the plot: Beatriz and Tomas are two teenagers who have been in love since childhood. Suddenly Indonesian troops invade the country. Eventually the Indonesians execute the entire male population of the village. Beatriz can’t find the body of her husband among the hundreds of corpses by the river, which leaves viewers with a glimmer of hope. She soon gives birth to a child fathered by her missing husband. Time passes. Timor becomes independent. Beatriz finally gives up hope and flips over the plate, which means her husband is dead. Sixteen years later, Tomas returns. Once a timid, scrawny boy, he has now become a super-macho. Beatrice is somewhat hesitant, but eventually accepts the war veteran’s courtship. Yet something keeps bothering her. He’s different somehow. Not the Tomas she knew and lost. Tomas keeps trying to persuade Beatrice, but flipping the plate over again is as difficult as bringing someone back from the dead. A special ritual is required, and it isn’t taken lightly. While Beatriz is thinking about it, she realizes that Tomas isn’t Tomas—he’s an impostor. And she kicks him out. The moral of the story is: once the plate has been flipped over, there’s nothing you can do. Life goes on. |