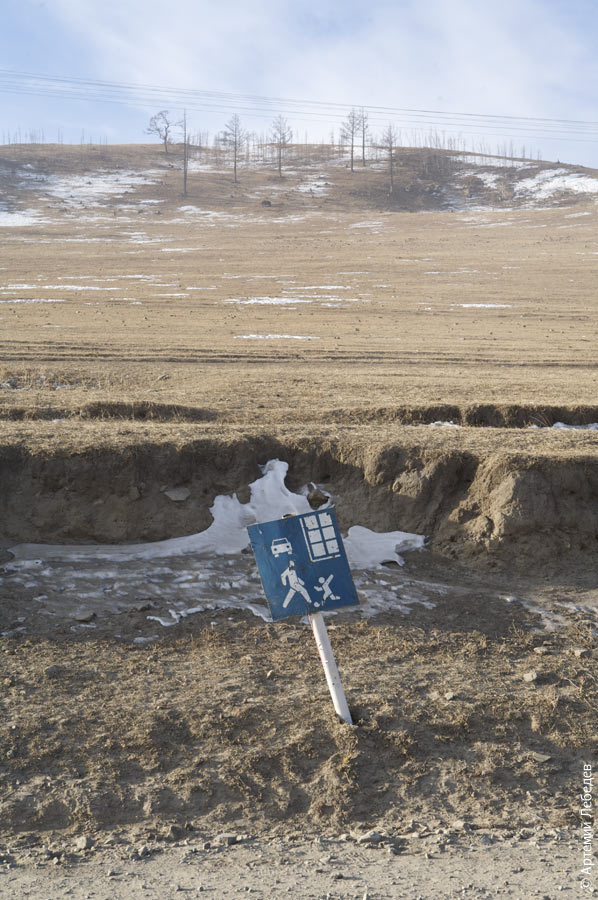

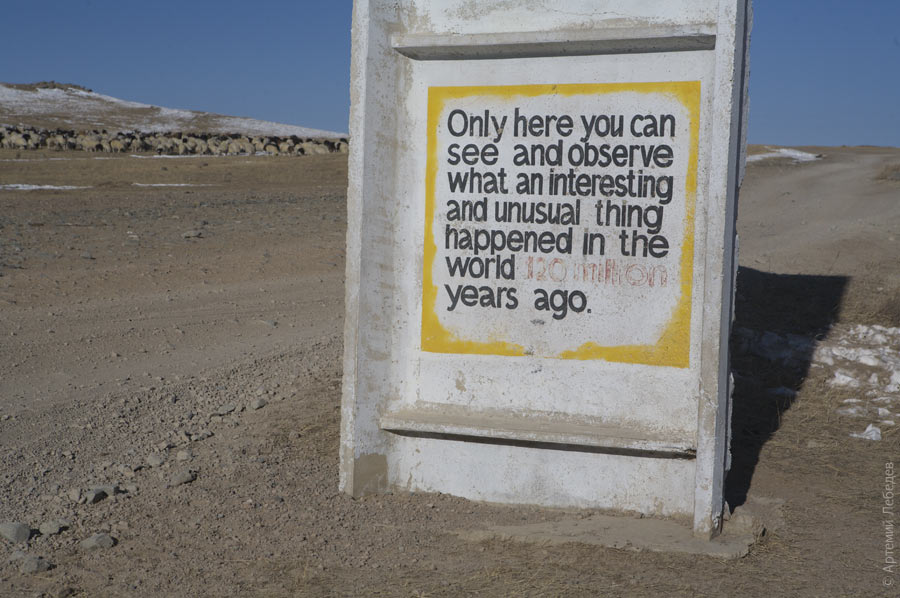

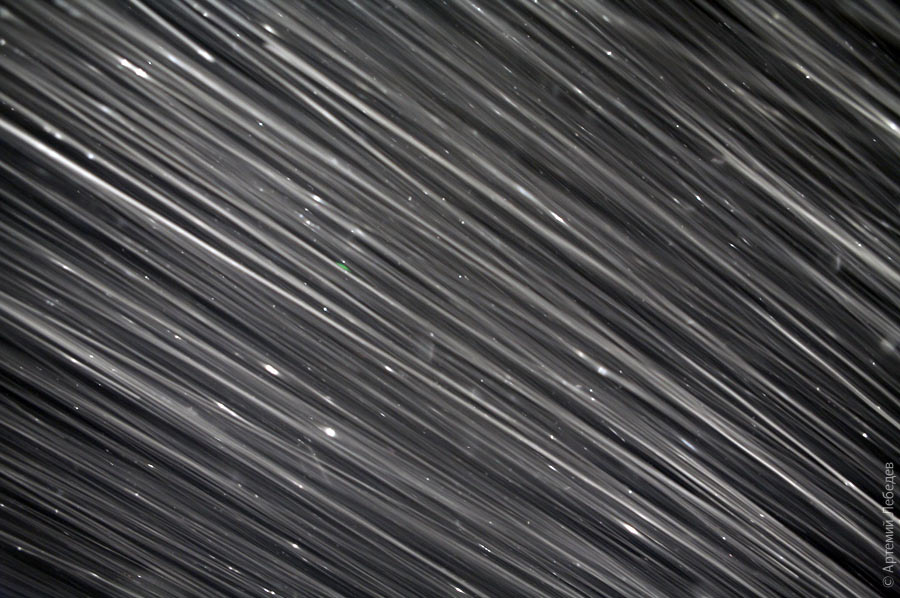

Ethnographic Expedition 2008. Part XIINovember 21–27, 2008 UlaanbaatarMapFinally.  Repairing the engine, replacing the oil cooler, intercooler and rear shock absorber plus other minor miscellanea came out to an astronomical sum. The only official Land Rover dealer in all of Mongolia, a company by the name of Wagner, charged me five times the cost of the tools needed to assemble the engine. This was no mistake: the owner of a Land Rover vehicle is expected to not only pay but to significantly overpay for things he doesn’t even need. They just forget to mention that in the ads. I decided not to spend the night in Ulaanbaatar. I had lunch with my Mongolian friend who’d been helping me non-stop this entire time and then set out westward. I had just three weeks to drive across Mongolia and Kazakhstan and return to Moscow via Astrakhan. The sun sets early this time of year, around six. It’s not a good idea to drive alone after dark: you never know what sort of potholes you might run into. My first overnight stop is in the middle of the steppe. It’s —20°C outside, so my tent is useless—at this point, the only place you can sleep is in the car. I watch a movie on my laptop, wash it down with whiskey and catch some z’s half sitting up in my sleeping bag. Rise at six, eat a breakfast of instant ramen and a Snickers bar with tea, watch the sunrise—and hit the road again.  Several GPS navigators I borrowed for a test drive are helping me find the way. They either don’t have maps of Mongolia at all or have bad ones, but it’s still more interesting than using a regular compass.  Driving around Mongolia is a lot of fun. Oftentimes, a village with five homes will have two competing gas stations right across the road from each other.  I’d managed to get about 250 kilometers from Ulaanbaatar and was driving on fairly even ground when Moumousique’s engine came loose for the fourth time (the new engine bracket, which had been shipped to Blagoveshchensk from London, had cracked). For the fourth time, I felt the familiar vibration inside the car. For the fourth time, the boot had come off one of the CV joints. My dream of driving across Kazakhstan went up in smoke. I had zero desire to go back to the crappy authorized dealership where they took two months to repair my car and charged me an insane amount for the privilege. I needed to get to the Russian border at any cost. After all, it was only about fifteen hundred kilometers to Altai, which is where I was headed. So I continued onwards, at a speed of about 20 km/h. I needed to get to a city called Tsetserleg, where I assumed I would find a mechanic who could put a wooden plank or something under the engine so that it wasn’t being held in place by just one bracket. Driving around Mongolia is very conducive to adopting a philosophical take on things.  In some random village, completely out of the blue, I drove into a dangling power line. I almost—after many years of successfully not doing so—shit my pants. In the rearview mirror, I could see the line going up to the utility poles. I backed up, but it managed to get snagged on the trunk. What part of the car should you not touch at this particular moment to avoid getting fried? I pulled to the side to try and get the line off the trunk, which worked. But it got snagged and wound around my rear axle instead. A bunch of cows observed dispassionately as the whole scene unfolded.  Strangely enough, all the grazing animals in Mongolia are afraid of cars. If you’re driving and see an entire herd on the road ahead of you, you don’t even have to slow down—they’ll all scatter soon enough. Cows, horses, sheep—they’ll all run away. Whereas in places like India, you can honk your heart out and not a single one of those jerks will so much as turn its head. The entire ethnographic expedition had come down to a simple task: getting a three-ton hunk of scrap metal out of the cold steppe. I wouldn’t have been able to achieve this without daily help from all sorts of people. Mongolians are surprisingly compassionate and have an innate tendency to help travelers—if not with engine repairs, then at least with a place to sleep. No one speaks Russian in the villages and small towns. But if you flag down someone with an SUV and say, „Zasvar?“ (repair), they’ll inevitably take you to their mechanic. TsetserlegMap I got lucky: the mechanic in Tsetserleg knew a whole ten words in English and promised to put a wood plank under the engine by the next day. A traffic light was once installed in this city for some unknown reason but now stands with its power line wrapped around the pole where it belongs.  A financial puzzle lay in store for me here. My car has broken down; I’m out of gas; I need food and a place to sleep. I’m out of tugriks. I have one hundred-dollar bill left over from the wad of money with which I’d arrived at the official Land Rover dealership. The machine rejects this bill as counterfeit. I have 15 thousand rubles, which are about as useful as Monopoly money here. The banks that are open don’t exchange rubles and won’t take my hundred-dollar bill. The only ATM in town is out of order. No one accepts cards, either. I propose that readers try to come up with their own solution to this conundrum. Meanwhile, I’ll just enjoy an ad for a wireless provider.  Feast my eyes on a frozen stream.  Photograph some excellent signs.  Add to my collection of trash cans.  Marvel at a former book pavilion.  BOOKS Ponder the combination of a swastika with Cyrillic script.  And not even notice the time fly by until morning comes and it’s time to go fetch the car.  The car is ready; I can get going.  Soon after Tsetserleg, a perfect paved road begins. It lasts for exactly 15 kilometers. There won’t be any more asphalt until the Russian border. Mongolia has many facets.  Only here you can see and observe what an interesting and unusual thing happened in the world 120 million years ago. It’s absolutely true.  I drove another hundred kilometers or so, the wooden plank fell out from under the engine, and the drive shaft started emitting infernal sounds. Some part of the CV joint had gotten crushed, and the car began to act jumpy on level ground as a result. I definitely didn’t like any of this: the border was still far away. I needed to replace the piece of wood. TariatMapBarely made it.  There’s no auto repair shop here, only a tire shop. The guys there took a good look at the wrecked drive, clicked their tongues, then went back to their tires and stopped paying attention to me entirely. It’s like how characters sometimes act in adventure games when you try to interact with them too early. In the end, I found a guy who supposedly had a truck. The truck turned out to be too small, and the price to be towed to the border too high. But that’s ok—I was offered food, tea (with milk and fat) and a spot to sleep, in the same room as the rest of the family (it was —10 in the guest room). One guy lifted the engine with a pipe, the other placed wood planks underneath.  The next day, I found myself in the Mongolian 19th century. Nothing disturbed the leisurely pace of life here.  The nomads were heading somewhere. Their personal belongings were packed up on carts with wooden wheels. Tires hadn’t been invented yet.  The map seemed to indicate that there was a shorter route to Russia, via Tuva. A road on the Russian side, marked „M-54 Yenisei,“ would supposedly take me straight to Krasnoyarsk.  I just needed to make sure I didn’t miss the turnoff.  There was more and more snow outside.  TosontsengelMapThere’s a police post on the road right before you enter the village of Tosontsengel. Every non-local gets shaken down for a bribe here, just for passing through. The guy with Tuvan plates in front of me was being hassled for a long time. I decided to follow him.  Night fell. A blizzard started up. The car was driving softly over the snow. And suddenly it stopped. The engine’s working, the heater’s working, but the rotation isn’t getting as far as the wheels. I’ve been driving for 20 hours straight without any stops or sleep at this point. Moumousique is glued to the spot right in the middle of the road in the middle of the mountains in the middle of the night. The view out the window:  I got lucky—after a while, a jeep turned up and agreed to give me a tow to the nearest village.  AsgatynMapI slept in a room that already had fifteen other people in it. In Mongolia, you completely forget that a room can have just one occupant; sleep is always a group activity here. Dogs aren’t allowed inside the house, by the way, and they’re encrusted with snow by morning.  Moumousique got dropped off in an enclosed yard with some sheep huddling by the fence. The Tuvan van was also parked here.  The van’s occupants turned out to be a Russian guy and three Tuvan women. One of the women owned the trailer, which she was using to transport things she had bought in Mongolia for her café in Kyzyl: foam ceiling tiles, lighting and sound equipment, drapes of some kind. She was nice enough to give me the number of her son-in-law in Ulaanbaatar, who spoke Russian and agreed to explain to the locals that I needed a truck. I had expected to get to the border by evening—it was only a hundred and fifty kilometers or so away. But if you want to get something today in Mongolia, you should probably reschedule your expectations for the day after tomorrow. I was told that the truck was supposedly on its way. The first floor of the guesthouse is a cross between a grocery store and a cafeteria. They make delicious meat soup here. Meat is something Mongolians eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I finished yet another book and went out into the yard. Out of curiosity, I popped the hood and took a look at the coolant tank. It was full of engine oil again. In other words, the thing that took two months to repair had happened once again—two liquids not meant to be mixed had gotten mixed somewhere. Meanwhile, the owner tackled a sheep in the yard.  He pinned it to the ground, made an incision in its belly, and pulled out some entrails. His leg held down its body while his hand kept its jaws closed. The sheep moaned for a minute or two and then peacefully passed into the next world.  All the men joined in on the action. They caught sheep around the yard, threw them down in the corner by the fence and skillfully slaughtered them. The lower legs are broken off and discarded, the head is cut off, the offal goes to the dogs, the hide is removed on the spot, and the meat is taken into the house, where they make delicious meat soup.  At this point, the van with the Tuvan women returned. Apparently, the overpasses were covered with snow and had gotten icy, and a vehicle with a trailer couldn’t get through. So the trailer and its owner were brought back. My ZIL truck arrived. I made the woman an offer: she could load her trailer in the back and chip in for the expenses. And that’s when the Tuvan woman underwent a complete transformation, revealing every facet of the complex Tuvan character. She declared that, in that case, she would take the truck herself and let me find another one. Subsequent encounters with other Tuvans demonstrated that there does indeed exist an entire ethnicity of unpleasant individuals on this earth. This observation diverged to some degree with my conviction that every ethnicity has only certain unpleasant representatives. I hitched Moumousique to the truck with a cable, put on my headphones, pulled out a jar of sour cherry preserves and continued onwards.  The truck got as far as the village of Bayantes before stopping for the night. I ended up having to sleep in the same yurt as the driver and the nefarious Tuvan woman. Sixty kilometers remained until the border.  In the morning, the driver announced that he would go no further, but that he had found some other truck going the same way. We dragged the woman’s trailer over and re-hitched my car. About five kilometers later, it became apparent that I couldn’t even be towed—my drive shaft was so warped that it was likely to get jammed at any moment, at which point the only way to move me would be with a crane. We found a ditch. The only part of my car that was still working well was the winch. And it came in really handy. I managed to haul the carcass into the truck’s trailer.  The drive to the border took the entire day.  We were the first to cross the remaining mountain passes that night, so we had to keep getting out of the truck to shovel the road ahead of us. Tsagaan-TolgoiMapI spent the night at a Mongolian customs officer’s house. The traditional Mongolian boots, a cross between rubber rain boots and felt snow boots, always have curled toes.  A Chinese color print is an essential decoration in every Mongolian house or yurt.  In the morning, Moumousique was loaded out by yet another ditch.  A Mitsubishi towed me across the border, which felt like a scene from a surrealist film: just a checkpoint with nothing else for miles around.  My homeland graciously proposed that I leave my car by the dumpster. Since there was nothing else at all within a fifty-kilometer radius of the checkpoint, I asked the same guy in the SUV to give me a lift to the nearest village.  Back in the motherland. Finally. |