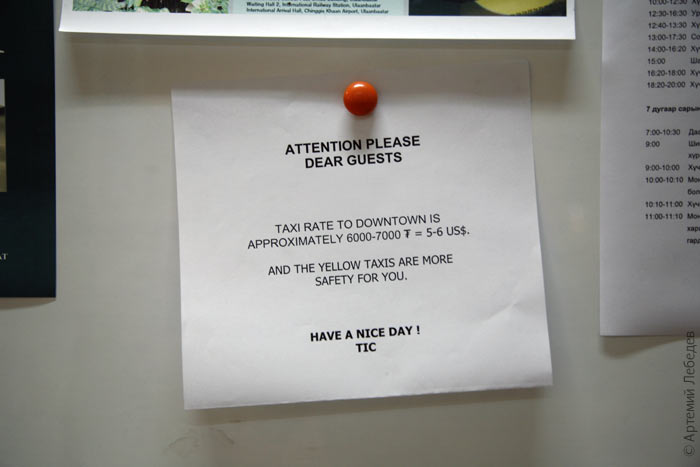

Mongolia. Part I. RealitiesMapJuly 19–30, 2006 “Mongol shuudan” means “Mongolian Mail”; Mongolians were banned from using last names for 70 years (their first cosmonaut chose the last name Cosmos for himself); Choibalsan was a Mongolian marshal. Ulan BatorMapThe flight from Moscow landed early in the morning.  At the airport they go to the trouble of warning foreigners that yellow taxis are safer, and also tell you what the taxi fare should be.  Russians gave their brother nation socialism and the Cyrillic alphabet, then promptly forgot all about Mongolia.  Kvas Some parts of Ulan Bator resemble Tashkent, others Novosibirsk, others still look like any other Soviet city with recent buildings.  The main difference compared to Soviet cities is that here the majority of window frames date back to when the buildings were first built, as well as the absence of air conditioners on the facades.  In every Russian city — in Moscow first and foremost — the locals feel it is their duty to install plastic windows (the only appropriate place for these is in a Turkish construction trailer — they were specifically designed so that workers could sleep after their shift without being disturbed by the sound of pneumatic drills) and a split air conditioning system (which provides about as much fresh air as you get from a refrigerator when you open its door). That’s why the architecture in all Russian cities is in the “beyond help” category. It’s possible that the people of Ulan Bator would very much like to ruin their buildings, but they just don’t have the money. The only familiar signs are the 6×3 roadside billboards, which should’ve been banned by a UN resolution a long time ago.  It’s all my family needs The ads on the lampposts are round without exception. You don’t see any oblong ads.  They smoke everywhere, in fact even the monuments smoke. The only place where we weren’t allowed to smoke was in a five-star yurt, and even that was only because the management turned out to be American.  Billiards is very popular in Mongolia. There are even billiard tables out in the street.  There’s a pawnbroker’s in every other building. By the way, in Mongolian a photocopier is known as a canon. Canon photocopiers were the first to appear in Mongolia, arriving together with the market economy. Before that Mongolians had no need for photocopiers, hence they didn’t have a word for them.  The police coat of arms is a circle with some writing in the Mongolian script (although they’ve had the Cyrillic alphabet since 1945). In the centre there’s an eagle showing his ID spread out flat. There are five cursors above his head. None of the locals could explain to me why the word “police” is always written in English.  The bedrock of local Mongolian colour is the half-destroyed, shabby state of everything. No one bats an eyelid at the wooden storm water drain grate in the central square.  Perfume counters have already taken over the first floor of the main department store, but on the whole the authentic atmosphere of the early 1980s still reigns here.  The “Lavazza” café’s trendy interior doesn’t stop the waitress from swatting flies right there on the plasma TV. By the way, Mongolians have taken up sumo wrestling and begun beating the Japanese. This year a Mongolian was crowned champion yet again.  They’re piss-poor drivers, which explains the constant traffic jams in the daytime. Every car takes up one and a half lanes and the most expensive car has priority. Time and time again drivers are surprised to learn that they aren’t the only ones on the road. Traffic controllers can be seen on tricky stretches of road. Their job can be summed up as follows: aggravate the traffic jams at intersections equipped with working traffic lights.  The most common mode of public transport is minivans, which are packed with unbelievably large numbers of people. They sit on top of one another, leaning their faces against the window as if they were studying something. An essential minivan attribute is someone touting for business in each one. This person also doubles as the cashier and the passenger compactor. They stand on the running boards at minivan stops, inviting sardines into their respective sardine cans.  As you walk down the street every one hundred metres or so you’ come across people with cordless phones. You can call a mobile or another landline (rates may vary). The operators wear anti-dust masks. For some reason they always look as if they fear a police raid, although there haven’t been any attempts to clamp down on this trade.  Word on the street is that local nightlife is vibrant, but I didn’t go to any clubs.  It turns out that Mongolians don’t have letterboxes in their homes. The post gets delivered to the post office — note the tautology. At the post office the post is distributed into numbered boxes. In contrast to Russia, subscription services didn’t die out after perestroika. A common way of getting the papers delivered is a subscription at your place of work: once a day a courier goes to the local post office branch and picks up everyone’s post.  Addresses aren’t commonly used in Mongolia. Most people remember what their street is called — it’s entirely possible that their knowledge of urban toponymy ends there. Here’s a standard description: “the third green building behind the central co-op store”. Similar means are used to describe where exactly in the boundless Mongolian expanse a given nomadic family is staying this particular year.  A blue ribbon called a hadag is a sign of utmost respect. Half of all billboards on the way to the city use this motif in their design. A hadag is the most common type of souvenir, offering, talisman, and decoration. The ribbons are brought in from China.  Mongolians are very superstitious. No amount of civilization will change their attitudes towards tradition. For instance, you can find ovoo — a sacred mound of stones — next to every road (outside the city). Ovoo come in different sizes and unlike Mongolians they aren’t nomadic. Thick blankets of blue ribbons envelop them.  People might ask the ovoo to grant them a safe journey or thank the ovoo for something specific. This is the spot for finding communion with the sky. Making an offering is a must. You can leave a rock, a sheep’s skull, money, or food. Tradition permits the destitute to take an apple or a banknote ab ovoo.  When the road went around an ovoo on the left side, our driver honked his horn, a must. We found out that you have to go around an ovoo on the left (so that the mound remains on your right). I placed 100 tugriks into the ovoo and asked for rain. The sky heard me loud and clear, it rained every day for the remainder of our trip. In Mongolian “huyag” means carapace, “huiten” means cold, while “hui-hui-hui” (“hui” means cock in Russian) is an interjection. Depending on the context it can mean “uh-oh” (when something falls or boils over) and “oi, you” (when trying to get someone’s attention). |